Exercise 18 - Object-oriented programming

Exercise 18 - Object-oriented programming¶

Andrew Valentine, Louis Moresi, louis.moresi@anu.edu.au

By now, you should be comfortable with the idea that variables have types, and often come with various functions and attributes ‘attached’ which can be accessed by using <variablename>.<functionname> or <variablename>.<attributename>. In this exercise, we will learn how we can implement our own data types and make use of this functionality.

Sometimes, the motivation for doing this will simply be ease of organisation. For example, suppose you have a collection of rock samples, and you wish to represent them in your program. You have various pieces of information about each rock in your collection, for example:

An ID number;

The location at which it was collected;

A brief description of the rock type (e.g. ‘Granite’);

Various geochemical measurements.

We have already seen various ways in which this information could be stored in a program, including tuples, dictionaries, and as a Pandas data frame. For many applications, these may be good choices. However, it is also possible to create a custom data type, which we will call RockSample, and encapsulate all the information about one physical rock within one Python ‘object’.

To do this, we need to write a class definition. This is an indented block beginning with the line class <ClassName>:, containing one or more functions. In particular, it will usually contain a function with the name __init__. This is the initialisation (or ‘constructor’) function, which gets called when we want to create a new ‘instance’ of the object.

For example, we might have a class definition:

class RockSample:

def __init__(self, idNumber, location, description, percentNickel=None, percentCopper=None):

self.idNumber = idNumber

self.location = location

self.description = description

self.percentNickel = percentNickel

self.percentCopper = percentCopper

Then we can use this to create variables representing each of our physical rock samples:

r1 = RockSample(1, (-35.3,149.1), 'Heavily altered sandstone')

r2 = RockSample(2, (-35.7, 148.9), 'Granite', percentCopper=0.01)

Notice that we use the class name as if it were a function, passing it the arguments required by __init__(). Now, we can access all our data as attributes of r1 and r2:

print(r1.description)

print(r2.percentNickel)

Attributes can be redefined, as necessary:

r1.percentNickel = 0.05

➤ Try it out.

# Try it here!

You have probably noticed that our __init__() function is defined as having four non-optional arguments, but when we call it to create a new variable, we only appear to pass three values to it. The first argument, self, represents the variable on the left of the equals sign. In other words, when we write

r1 = RockSample(1, (-35.3,149.1), 'Heavily altered sandstone')

we are effectively calling

RockSample.__init__(r1,1, (-35.3,149.1), 'Heavily altered sandstone')

(although writing it this way will not actually work). Within the __init__() function, lines like self.idNumber= idNumber attach attributes to the variable name. By convention, the variable name self is always used for this first argument, although it is technically possible to use any name here. Note that __init__() should not contain a return statement.

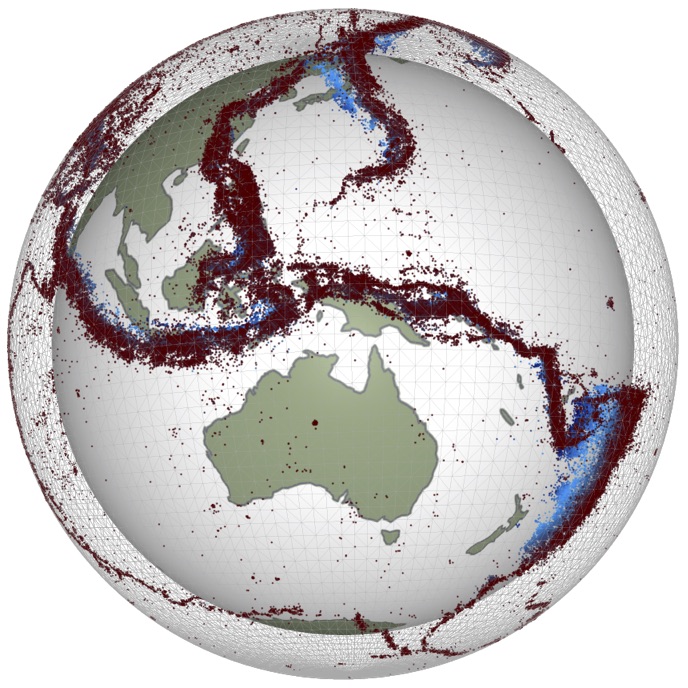

We can add other functions to the class, all of which should have self as the first argument. Functions in classes may return a value (by having a return statement as usual), but they can also modify the internal data in the class (i.e. set or change attributes attached to self) or have other ‘side-effects’. For example, we might write a plot_location() function, to create a map showing where the sample was collected.

class RockSample:

def __init__(self, idNumber, location, description, percentNickel=None, percentCopper=None):

self.idNumber = idNumber

self.location = location

self.description = description

self.percentNickel = percentNickel

self.percentCopper = percentCopper

def plot_location(self,...):

[...]

ax.plot(self.location[1],self.location[0],'x')

[...]

Then, we can call

r1.plot_location(...)

and a map will be generated.

➤ Write and test the plot_location() function.

# Try it here!

What have we gained by doing this? One benefit lies in data organisation: by encapsulating information in this way, we ensure that all our data about a physical sample is kept together. We can easily pass the entire RockSample object to a function, ensuring that all information is accessible within that function. This becomes particularly useful when developing large, complex programs, where one might have something like

def function_a(rock):

[...]

u = function_b(rock,...)

[...]

def function_b(rock):

[...]

v = function_c(rock,...)

[...]

def function_c(rock,...):

# The function that actually

# uses the attributes of rock

[...]

i.e., we pass rock down through several layers of function-call before we actually make use of the information it contains. By encapsulating everything within a class, we can write function_a and function_b without needing to think about what information function_c will be accessing. If we subsequently decide to change how function_c works, we can easily add new information to the class and access it inside function_c, without needing to make any modifications in function_a and function_b.

Employing classes can also be powerful in situations where we want to handle distinct classes of data in a unified way. For example, we might have two different models of mass spectrometer, which produce data files in different formats. By wrapping everything into classes, we can avoid our analysis code needing to know anything about the different machines:

class instrumentA:

def __init__(self,...):

[...]

def getExperimentDate(self,...):

# Read experiment date from data file

return date

[...]

class instrumentB:

def __init__(self,...):

[...]

def getExperimentDate(self,...):

# Read experiment date from data file

[...]

return date

[...]

def processData(instrument,...):

[...]

date = instrument.getExperimentDate()

[...]

inst = instrumentA(...)

processData(inst,...)

inst = instrumentB(...)

processData(inst,...)

The philosophy here is that the processData() function needs to know nothing about where or how the data is stored; it simply receives an instrument object from which it can ‘request’ any information that it requires. If in the future a new instrument is purchased, we only need to write a new instrumentC class containing the appropriate functions, and then all our existing analysis code will be ready to use.

Sometimes, we may wish to have two or more classes that have some functionality in common. This can be achieved by using subclasses and ‘inheritance’. First, we write the ‘parent’ class, containing the common parts.

class a:

def __init__(self, x,y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def product(self):

return self.x*self.y

This is a fully-functioning class, and we can create instanstances of it, e.g. p = a(3,4). However, we can also extend it by writing a subclass.

class b(a): # <=========================== (1)

def __init__(self,x,y,z):

a.__init__(self,x,y) # <========== (2)

self.z = z

def tripleProduct(self):

return self.product()*self.z # <== (3)

Objects of class b have all the functionality found in objects of class a, plus some additional features (specifically, the tripleProduct() function). Note three things:

When we define the subclass name, it is followed by the parent class name in brackets. It is possible to inherit from more than one parent class simultaneously, although this is unlikely to be used except in the most complex codes.

In the

__init__()function for the subclass, we need to explicitly call the__init__()function of the parent class(es).We can make use of functions and attributes from the parent class within the subclass.

➤ Try it for yourself.

# Try it here

Subclasses are not something you are likely to use often. However, they can occasionally be useful, especially if you want to modify one of the ‘standard’ Python classes. For example, you might choose to represent a dataset by creating a subclass of Python’s standard list type, adding additional attributes and functions specific to your dataset.

Finally, there are a number of ‘special’ functions you can add to any class. These are the function names with double underscores, such as __add__(), __str__(), __mul__() and so on. These allow your class to work with standard Python operations such as +, print and * act on your class. For example, we can modify our RockSample object to include a __str__() function, which should return a text string containing whatever information we deem useful:

class RockSample:

def __init__(self, idNumber, location, description, percentNickel=None, percentCopper=None):

self.idNumber = idNumber

self.location = location

self.description = description

self.percentNickel = percentNickel

self.percentCopper = percentCopper

def __str__(self):

if self.location[0]<0:

clat = 'S'

else:

clat = 'N'

if self.location[1]<0:

clon='W'

else:

clon='E'

return "%s from (%.2f%c, %.2f%c)"%(self.description,abs(self.location[0]),clat,abs(self.location[1]),clon)

Now, if r1 = RockSample(1, (-35.3,149.1), 'Heavily altered sandstone') then we can call print(r1) and see a meaningful message.

➤ Try it out.

# Try it here!

In Exercise 7, you wrote an encoder and decoder for the Caeser cipher.

➤ Rewrite your code to make use of classes.

Hint: Create a caesar class that contains at least three functions: __init__(), encode() and decode(). Put all of the ‘set-up’ code into __init__().

# Try it here!