Computational Geosciences

Contents

Computational Geosciences¶

Louis Moresi, Australian National University; Andrew Valentine, Durham University (formerly ANU); Navid Constantinou, Australian National University. Other authors have contributed material to this document (thank you !), see Acknowledgements for a list.

In this course, we are first going to touch on some basic principles of programming, discuss what it even means to program a computer, and then move on to get a feel for what a program looks like using the python programming language for all of our examples. We are going to work mostly online using the jupyter literate computing interface to python as our electronic lab notebook and we are going to learn by example.

We are also trying to learn good programming habits - like writing a plan for our software before leaping in, using reliable version control (especially when working in teams), writing tests, adopting a helpful, clear programming style.

There is a step-by-step guide to learning python programming and also a number of deeper-dives into topics of relevance to Earth Science.

Introduction¶

In the history of computing, the concept of “programming a computer” has evolved rapidly in conjuction with a rapid expansion in processing power, storage and communication speed. It is helpful to look back and think about this progression as we think about the aspects of computer programming that persist through all of this change.

We take for granted the rapid improvements in computing technology that mean computing power doubles every year or two by almost every practical measure (This has become known as Moore’s Law [Moo06]). This fact, more than anything else, has dictated the path to more and more high-level thinking in how computer programs are created.

Early electronic computers were expensive and not especially powerful. They understood a rudimentary set of instructions and it was a very specialised job to write the instructions for any complex task that could solve some useful problem with the limited resources of such machines. Ingenuity was a key requirement for a programmer human effort in careful program design paid off in speedy, mistake-free computation.

Fig. 1 CSIRAC was constructed by the Division of Radiophysics to the designs of Trevor Pearcey (pictured) and Maston Beard. This photo was taken on 5 November 1952. [Photo: CSIRO Archives]¶

As computing power advanced, the instructions understood by a computer could be expanded. In fact, it was no longer a waste of time and money to write computer programs in a human readable form and have the computer translate them to its own more basic instructions later. True programming begins in this way: creating a description of the operations that are going to be executed without having to know the underlying details of the machine that will be doing the computation.

It probably goes without saying that making that first abstract leap naturally leads to another and another. Programs become complex and it can be helpful to step up until we reach a level that does not deal with the details within a program but just treats it as a collection of operations that process information in a predictable manner. A library is a collection of operations that do a small number of jobs for several other programs to use but do little or nothing on their own.

Advancing computer power means that the computer does more of the work and allows a programmer to take a much higher-level view of the problem that needs to be solved. It also allows people to build and re-use very general libraries that have been thoroughly tested. It is usually not a problem that libraries do more than we need and this means that we don’t need to change any code in a library at the risk of breaking it.

At the very least, this means that, over time, we can expect software (programs) to grow more reliable and gain functionality as people fix and improve it because it is always being reused. The improvements in hardware are what make this possible.

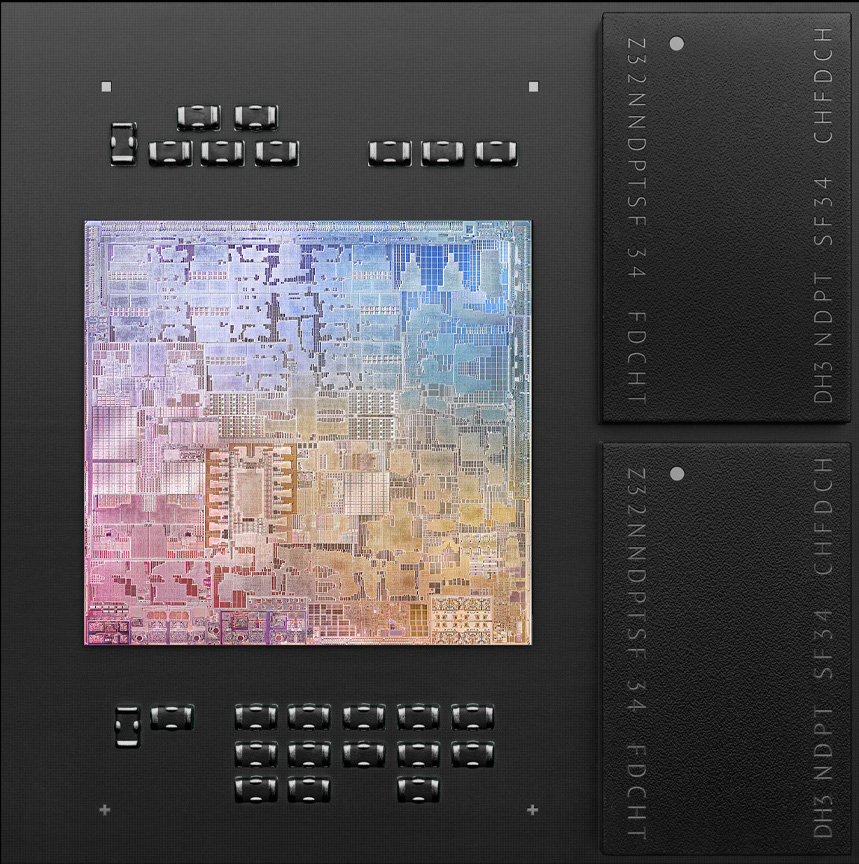

Fig. 2 Apple’s M1 chip has 16 billion transistors etched at a 5nm scale. It runs multiple different threads on the one chip and many of the subsystems that used to be on separate chips are integrated. It is not compatible with the previous generation of chips (it uses a different instruction set at the binary level) but it can emulate those chips when necessary and still has some speed advantage. This abundant power and storage means that you can concentrate on writing robust, flexible codes, not on puzzling over clever algorithms that are specially tuned for one particular architecture. Progress ! (Image copyright: Apple, 2020)¶

If the computer language that our software was written in is not the one we are using, no matter, we can simply write a translator of some kind and let the advancing hardware speeds and storage capacity make up for the extra cost. It is even possible to create software equivalents of the computer hardware (and the basic operating system) itself which makes it possible to create a computing “cloud” where the execution of your program may run anywhere or skip from machine to machine on demand including different hardware from where it started. This is another kind of re-use: making it possible to recreate or clone a running device at any time and receive identical results every single time.

Acknowledgements¶

This text and the accompanying examples were written for teaching computer programming to students at the University of Melbourne and the Austalian National University. We include teaching material from Dan Sandiford and Ben Mather as well as examples taken from the gallery / cookbook pages of some of the packages we use. Where we know the source, we try to cite the source correctly but we are happy to be corrected where we have missed something. A good way to let us know is to raise an issue on the GitHub repository associated with this book which can be found here.