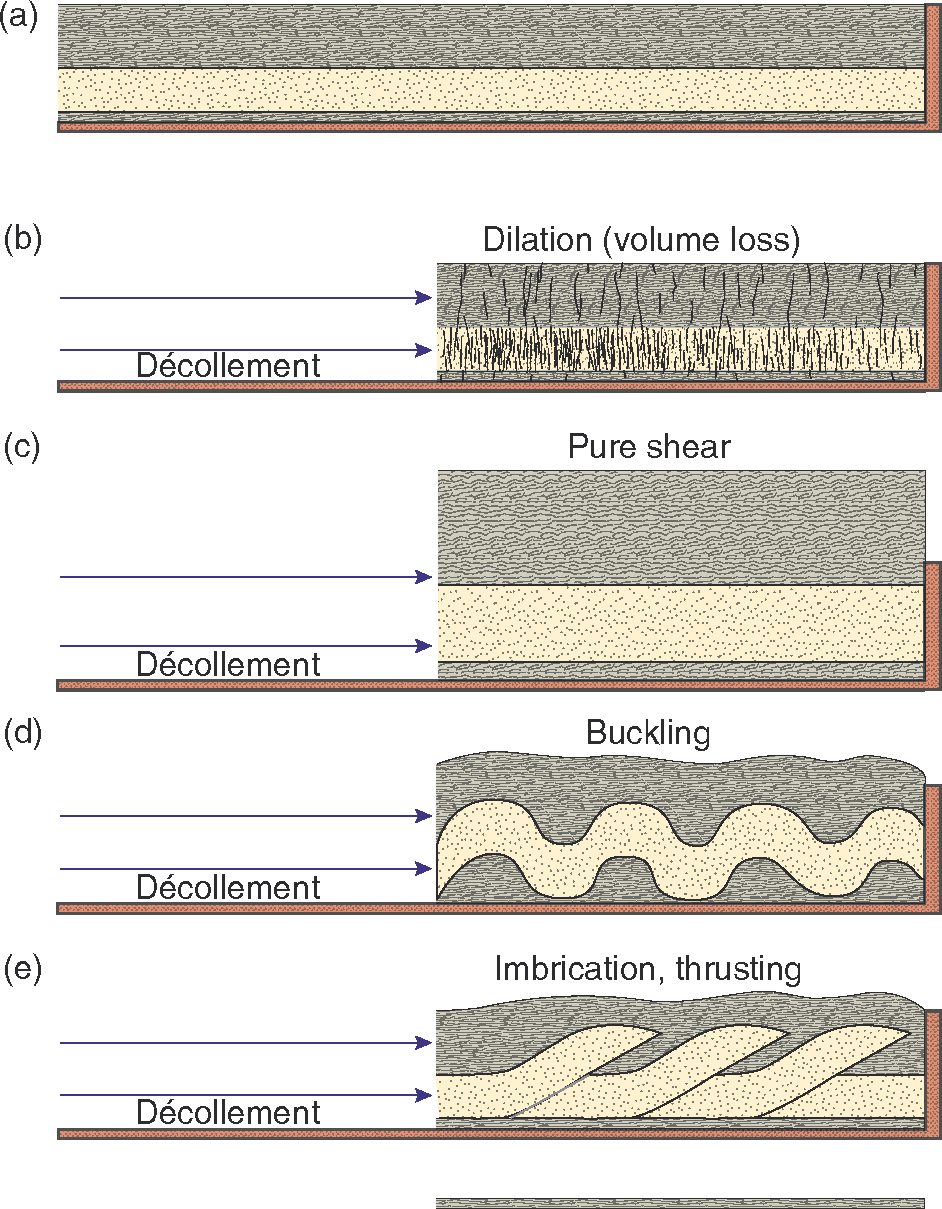

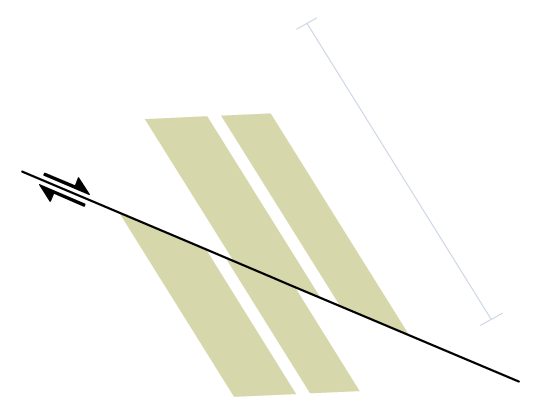

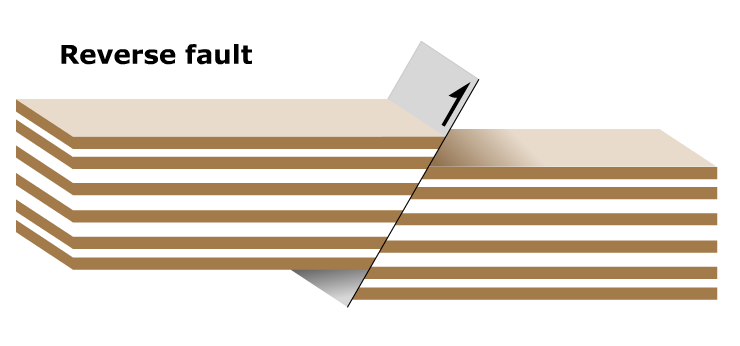

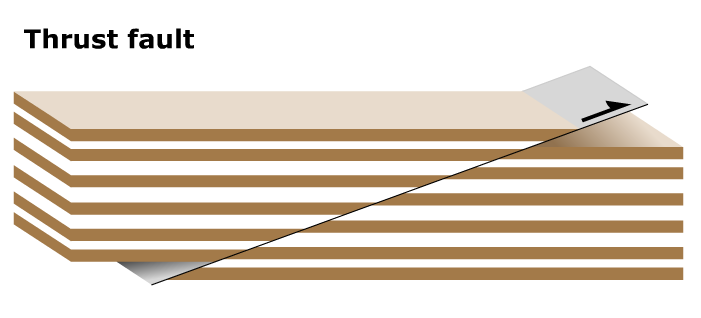

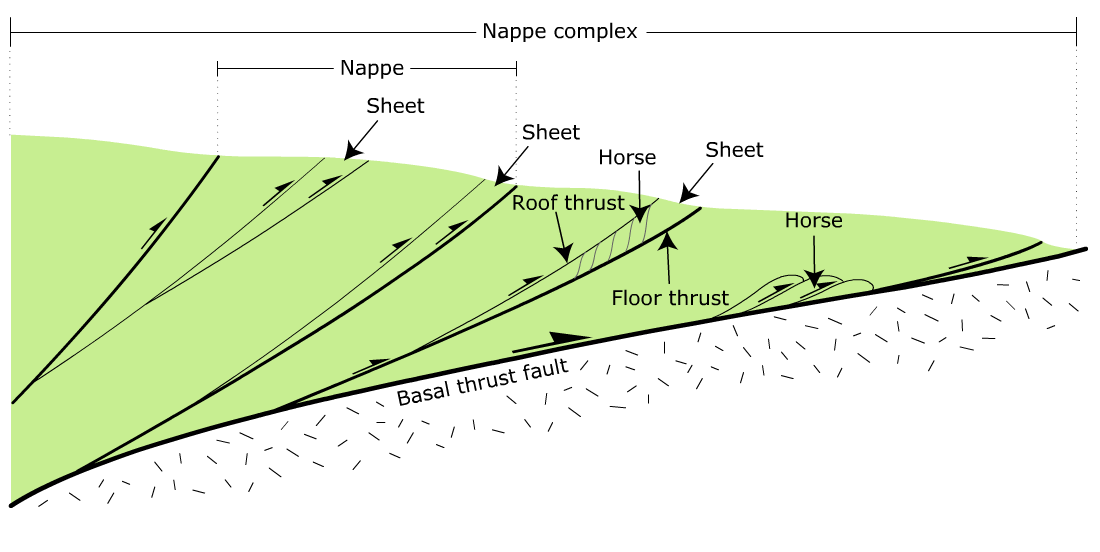

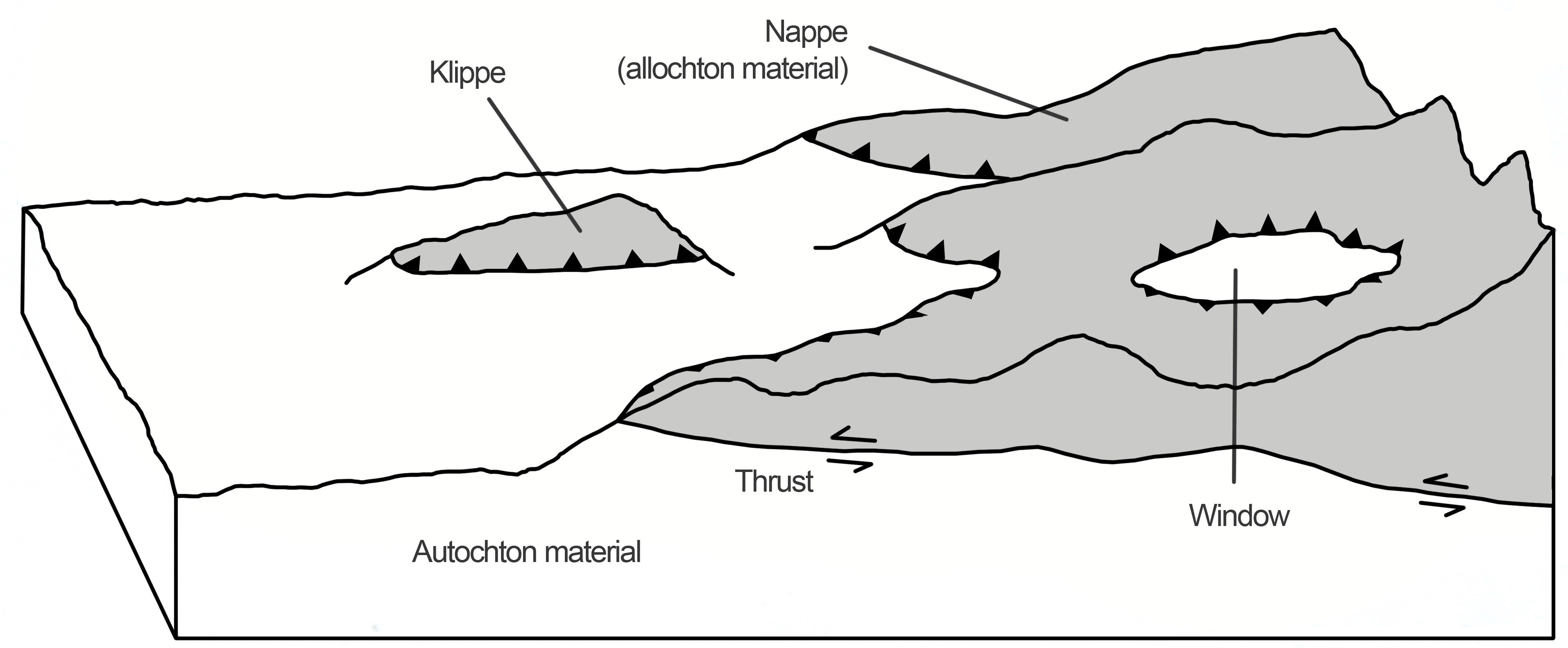

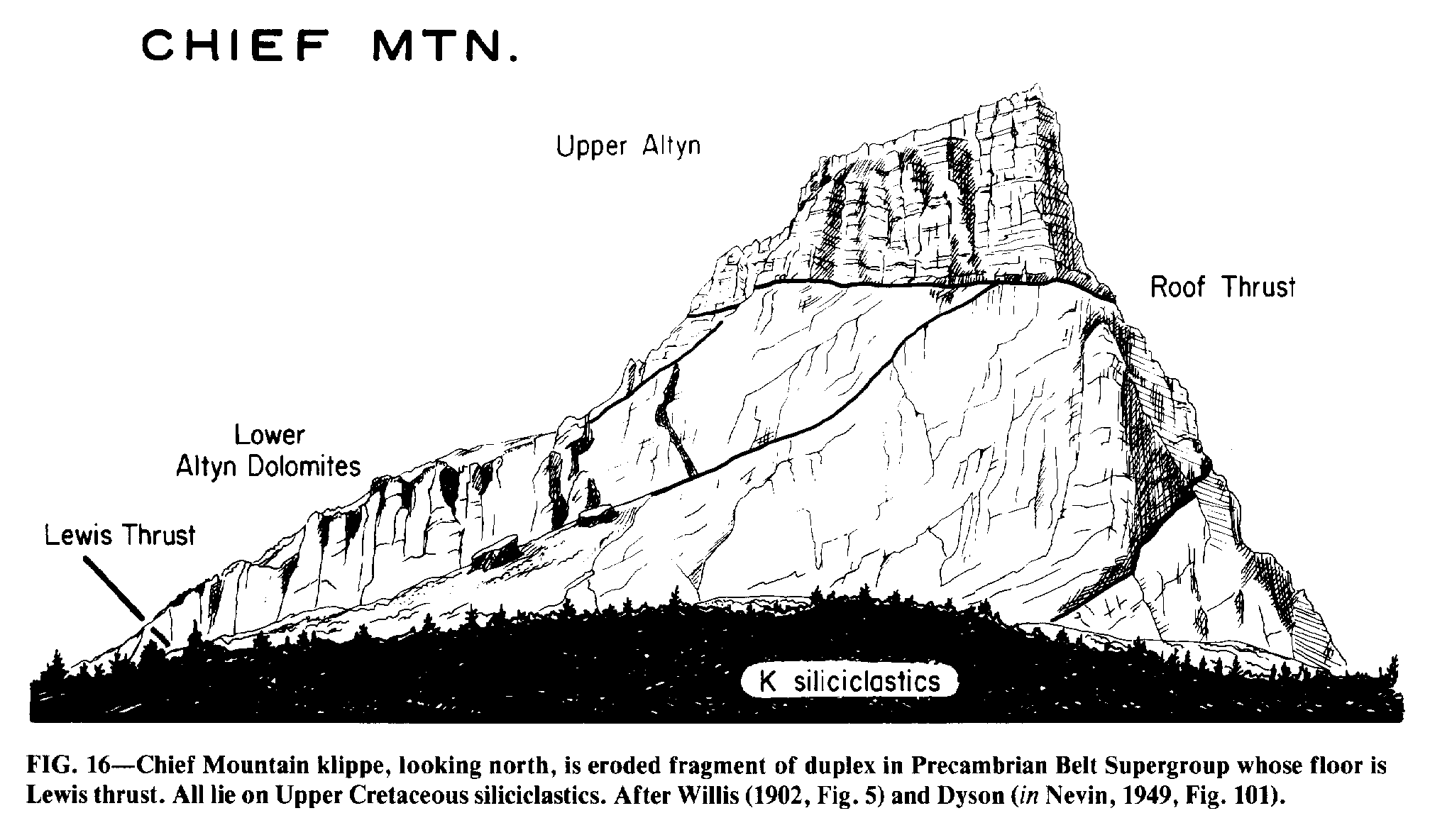

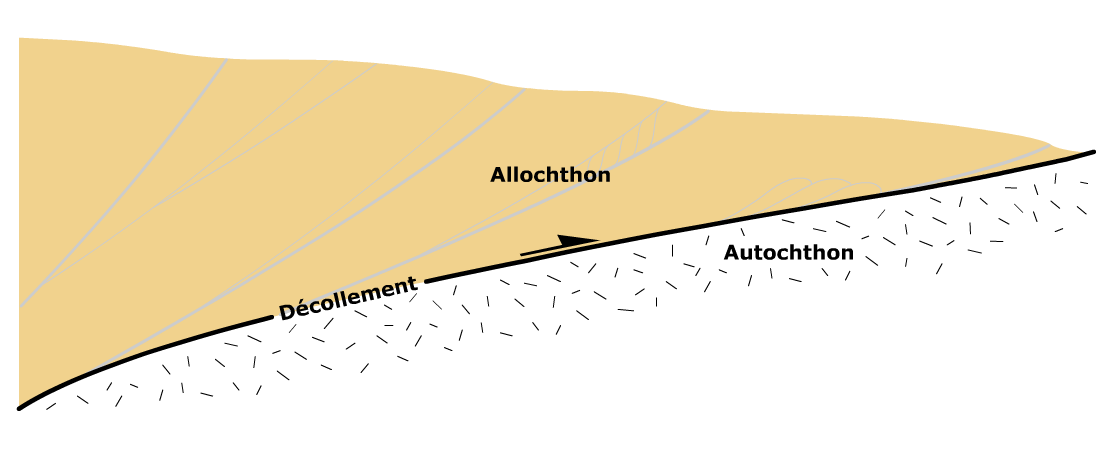

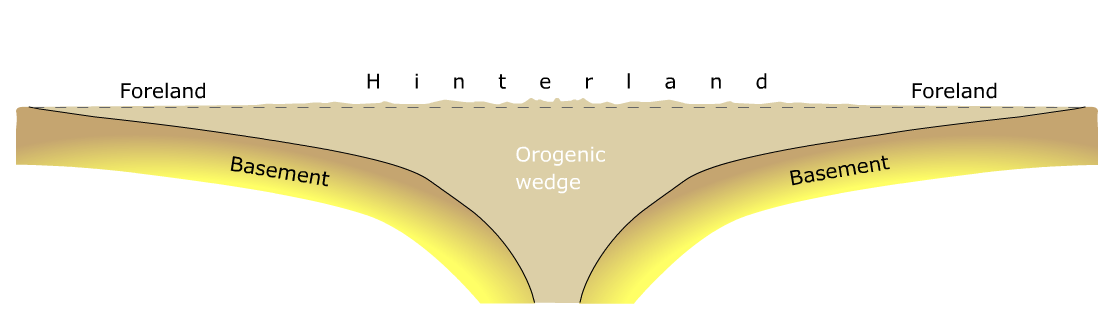

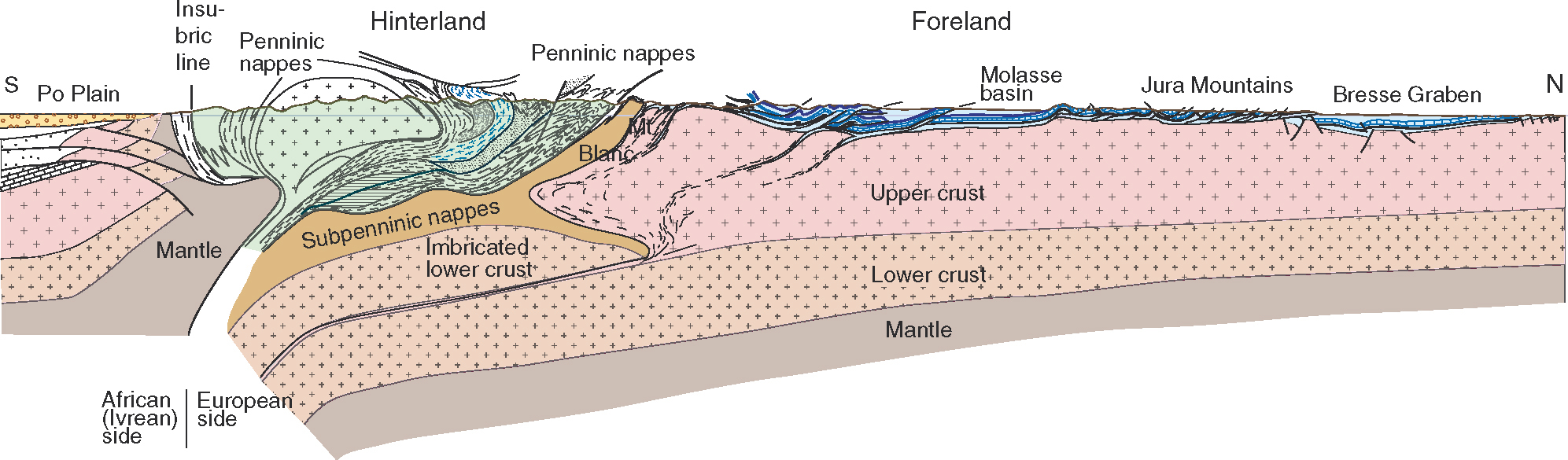

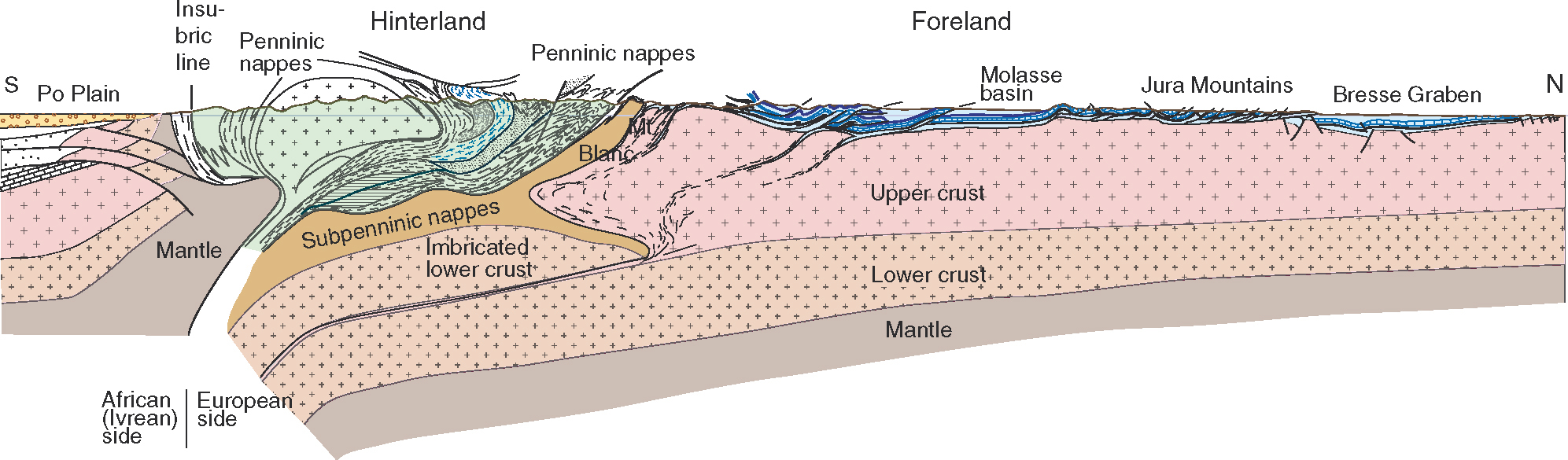

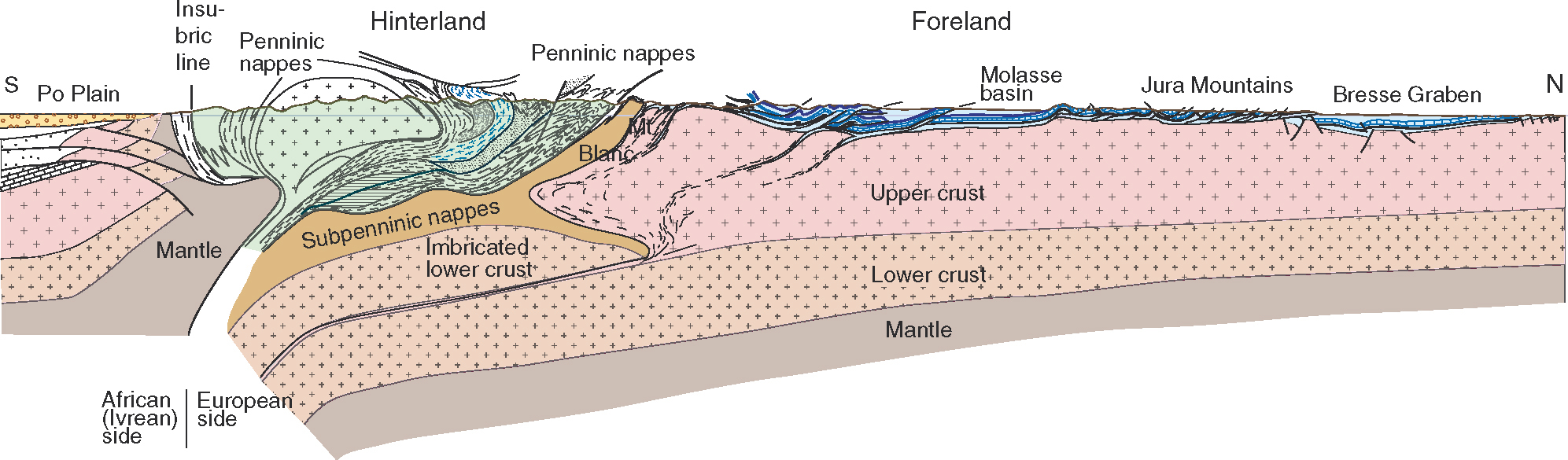

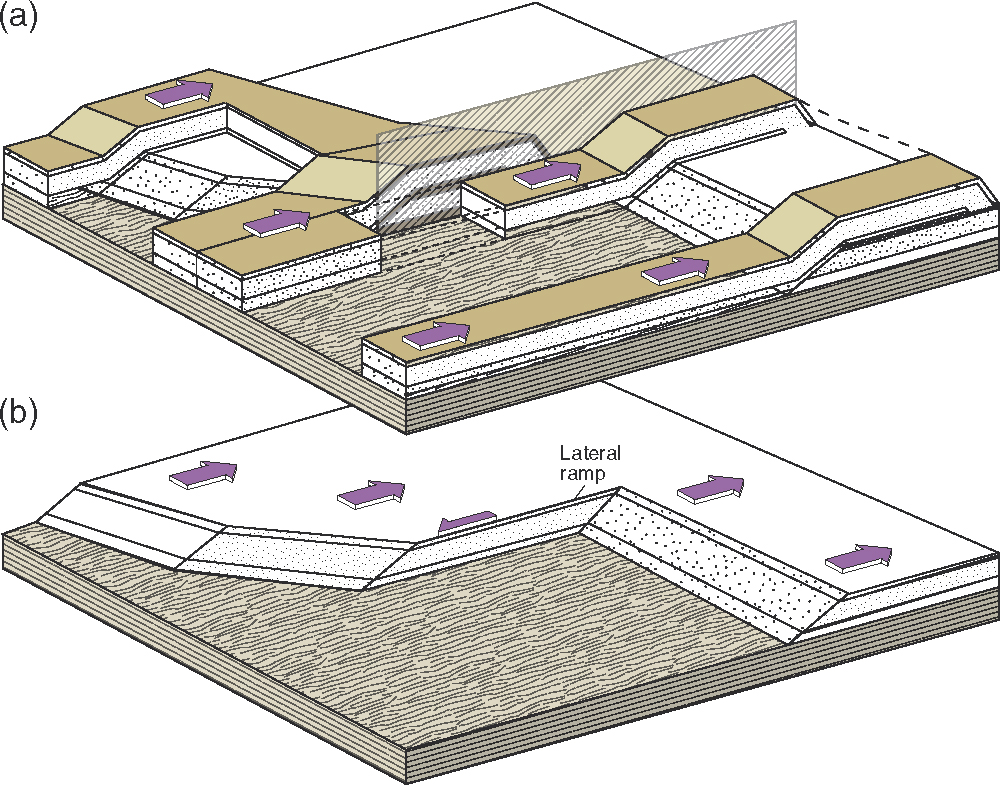

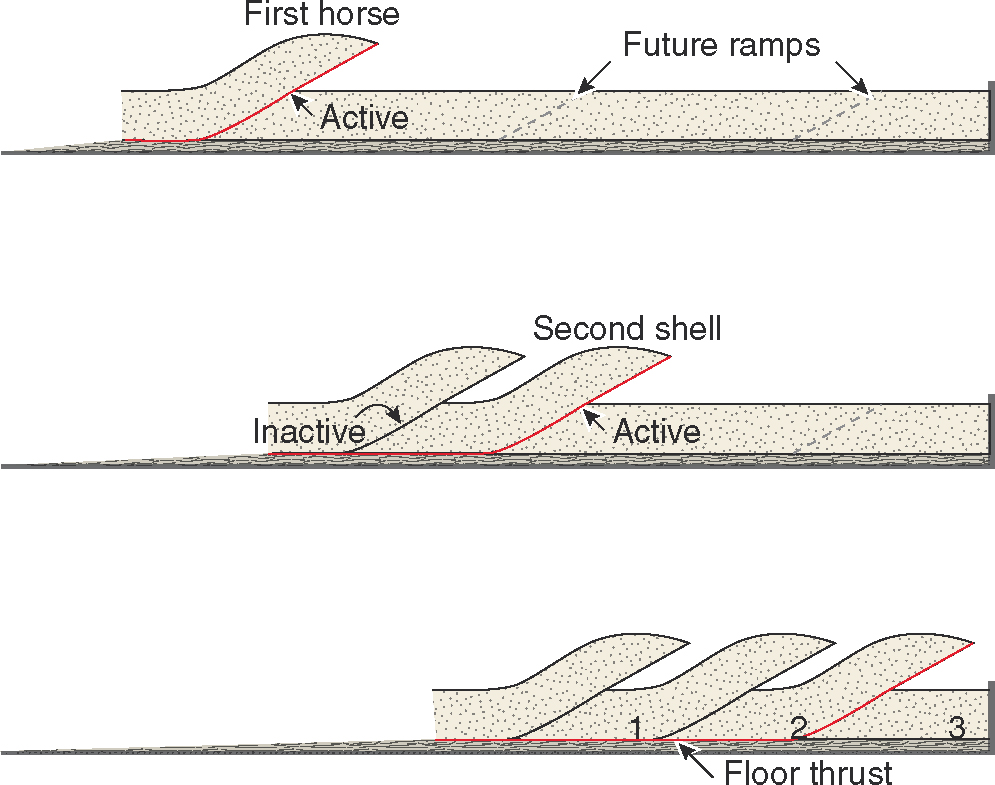

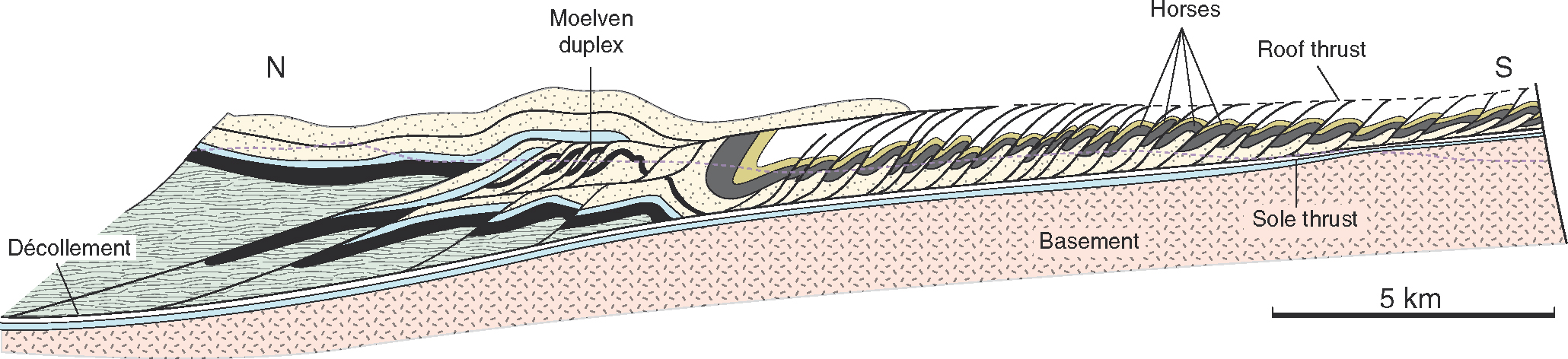

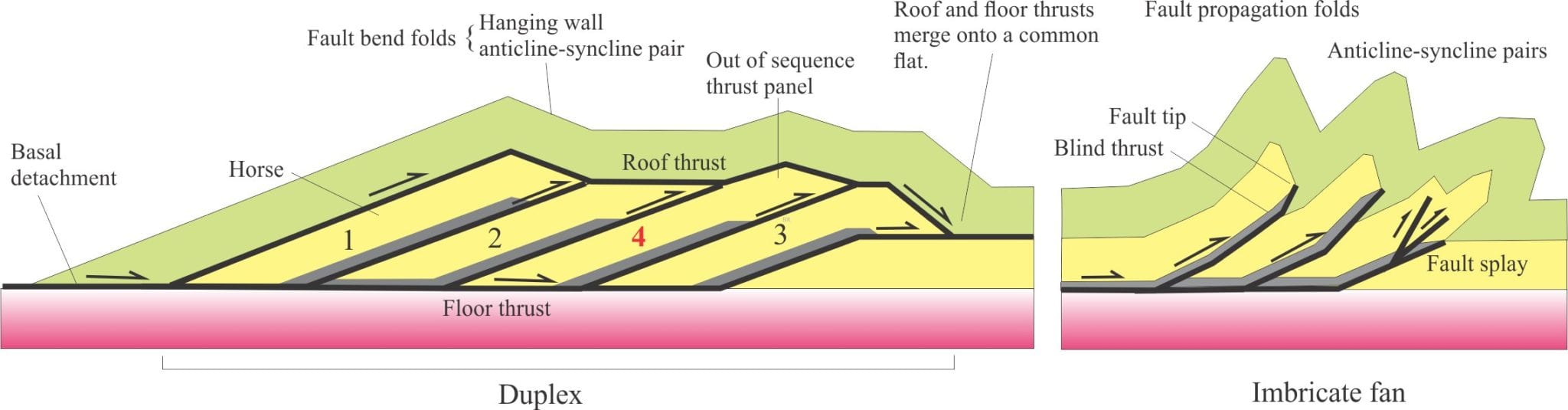

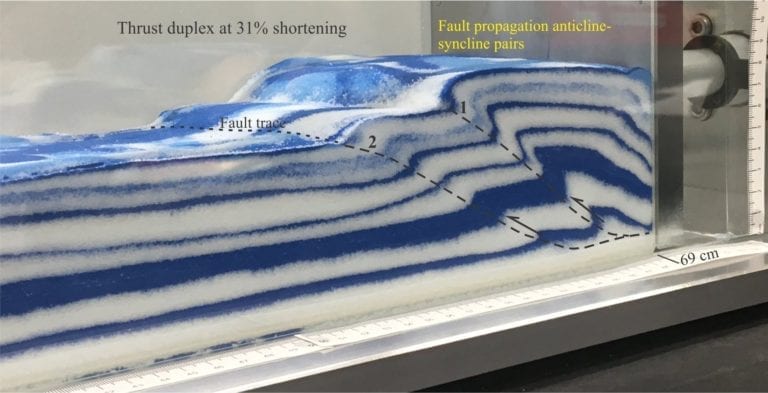

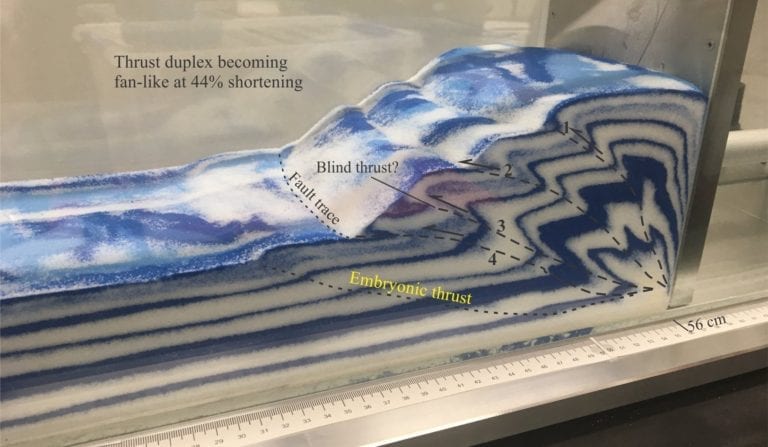

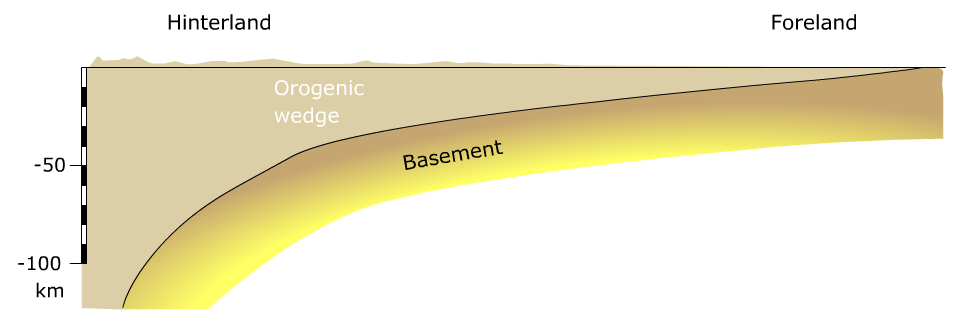

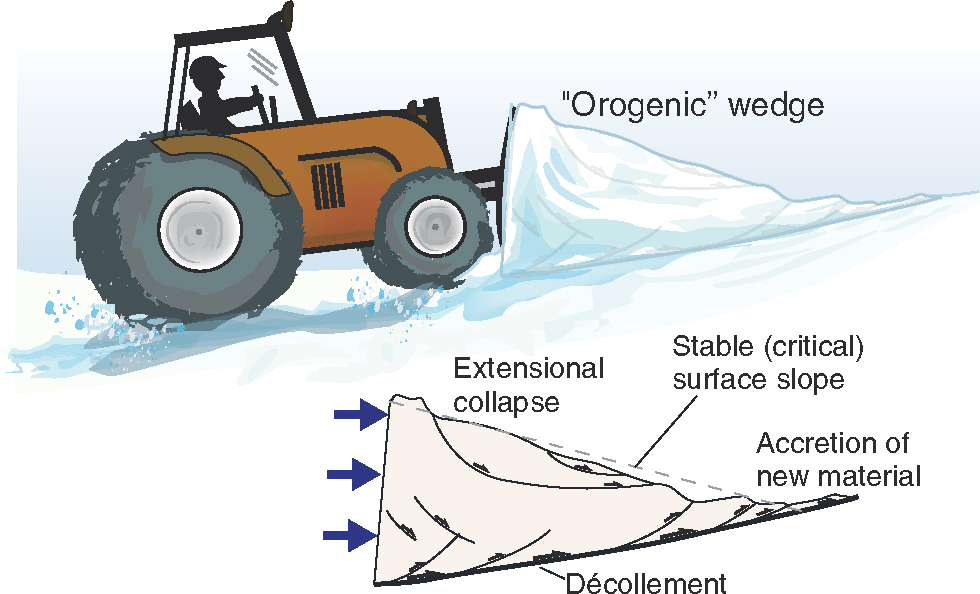

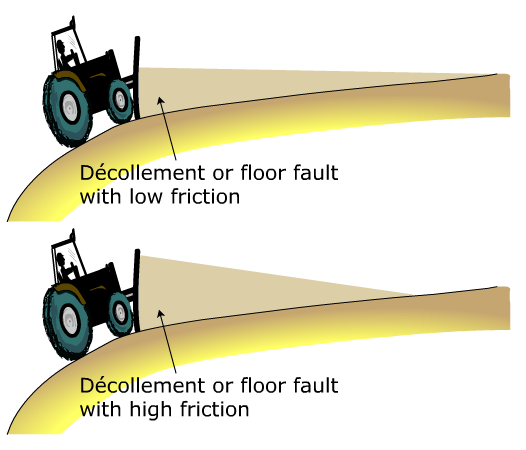

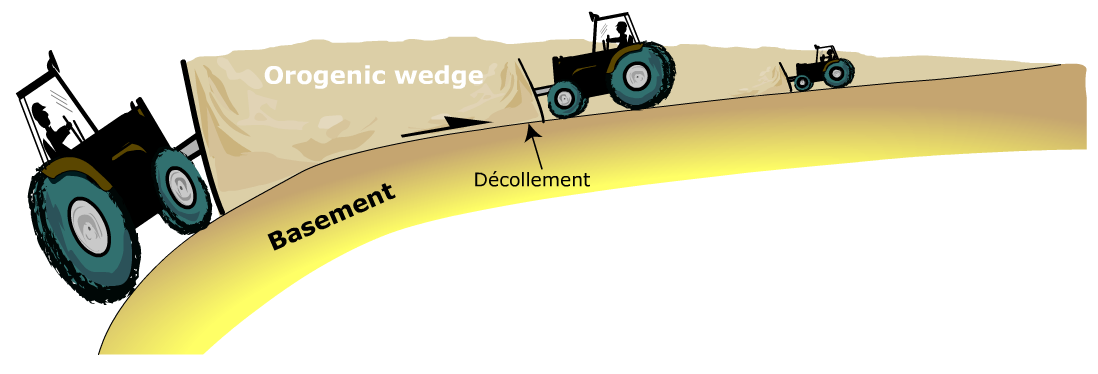

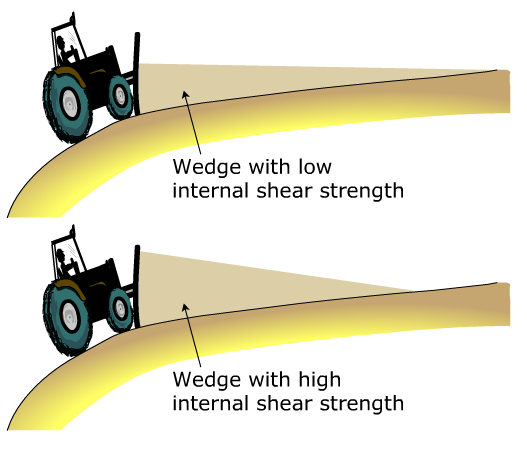

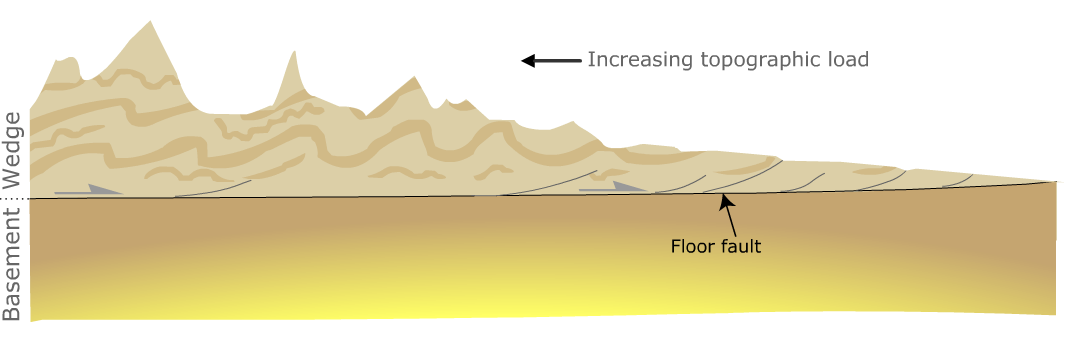

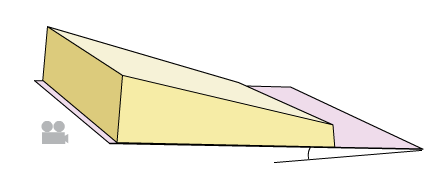

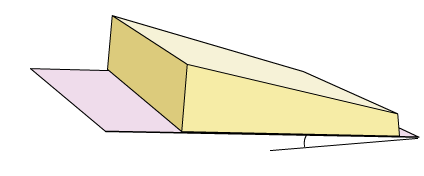

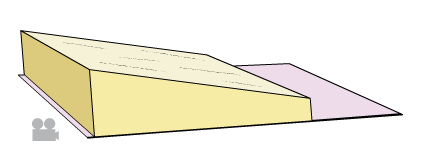

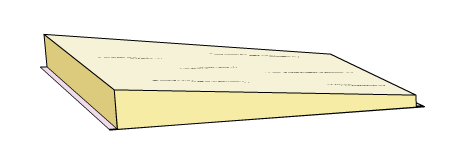

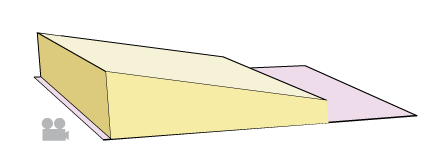

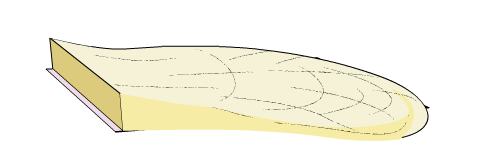

# EMSC 3002 ## Contractional regimes - **Louis Moresi** (convenor) - Chengxin Jiang (lecturer) - Romain Beucher (former lecturer) - Stephen Cox (curriculum advisor) Australian National University _**NB:** the course materials provided by the authors are open source under a creative commons licence. We acknowledge the contribution of the community in providing other materials and we endeavour to provide the correct attribution and citation. Please contact louis.moresi@anu.edu.au for updates and corrections._ <--o--> ## Resources 1. **Fossen, H, 2011.** *Structural Geology.* Cambridge University Press, 2nd Edition. 1. **McClay, K.R. 1991.** *The Mapping of Geological Structures.* John Wiley & Sons. 1. **Park, R.G., 1995.** *Foundations of Structural Geology.* Blackie & Sons Ltd. 1. **Davis, G.H. and Reynolds, S.J., 1996.** *Structural Geology of Rocks and Regions.* 2nd Edition, John Wiley & Sons. <!-- 1. **Hatcher, R.D., 1990.** *Structural Geology - Principles, Concepts, and Problems*, 2nd Edition, Prentice-Hall --> <!-- 1. **Ramsay, J.G. and Huber, M.I. 1983.** *Modern Structural Geology. Volume 1: Strain Analysis.* Academic Press. --> <!-- 1. **Ramsay, J.G. and Huber, M.I. 1987.** *Modern Structural Geology. Volume 2: Folds and Fractures.* Academic Press. --> <--o--> ## Intended learning outcomes <--o--> ## Contractional Structures **Contractional structures occur in any tectonic regime, but they are more common along convergent boundaries.** Understanding contractional structures is important for understanding formation of mountain belts in general, but also for improved oil and gas exploration methods, because many world's oil ressources are located in fold and thrust belts. <--o--> ## Contractional Structures **Contractional deformation structures when rocks are shortened by tectonic or gravitational forces** We find contractional faults and folds in: - All parts of collisional zones. - Accretionary prisms associated with subduction zones. - In gravitationally instable structures such as deltas and continental-margin sediments resting on weak mud or salt. <--o--> ## Contractional Structures **Shortening can be accomodated in different ways** <div> <div style="width:50%; float:left"> - Volume loss and formation of dissolution seams (pressure solution, e.g. stylolites), compaction etc. - Pure shear deformation where horizontal shortening is compensated by vertical thickening and where layers maintain their orientations. - Buckling of layers (folding). - Contractional faults and related folds structures. </div> <div style="width:40%; float:right; margin-left:50px;">  <!-- .element style="float: right" width="90%" --> </div> </div> <--o--> <!-- .slide: data-background="Module-ii-Figures-Structural-Geology-And-Crustal-Deformation/ContractionalStructures/ThrustFault.jpg" --> <--o--> ## Contractional faults **Contractional** faults are faults that accommodate contraction or shortening. In most cases, contrational faults correspond to **reverse** or **thrust** faults which accommodate shortening in the horizontal direction.  <!-- .element style="float: left" width="50%" -->  <!-- .element style="float: right" width="50%" --> <--o--> ## Contractional faults Note that contractional faults may include normal and oblique faults. In the example below the normal fault accommodate layer-parrallel shortening.  <!-- .element style="float: left" width="50%" -->  <!-- .element style="float: right" width="50%" --> <--o--> ## Thrusts Faults and reverse Faults Contraction in the horizontal plane, or tectonic contraction, is associated with formation of **reverse** and **thrust faults**. **Thrust faults** are **reverse faults** with shallow dip. (less than 30 degrees)  <!-- .element style="float: left" width="50%" -->  <!-- .element style="float: right" width="50%" --> <--o--> ## Thrust Faults  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:right; margin-left:50px;" --> A **thrust** is a low angle fault or shear-zone where the hanging wall has been transported over the footwall Thrusts faults bring older rocks on top of youger rocks, and rocks of higher metamorphic grade on top of rocks of lower metamorphic grade. *Stratigraphy and Metamorphic grade can both be used to map thrusts... Stratigraphic control is particularly important* *Photo: Chief Mountain, Montana. pre-Cambrian limestones over Cretaceous shales.* <--o--> <!-- .slide: data-background="Module-ii-Figures-Structural-Geology-And-Crustal-Deformation/ContractionalStructures/Chief_Mountain.jpg" --> <--o--> ## Thrust Faults and Tectonic Units ### Nappe Terminology  <!-- .element style="width:60%;float:right; margin-left:50px;" --> **Thrust nappes** consist of one or several subordinate **Thrust sheets** that have a common diplacement history. The smallest tectonic units originating within the pile is called a **horse** Nappes, sheets and horses are bounded at their base by a **sole thrust** or **floor thrust** and at the top by a **roof thrust** Nappes are thin compared to their lateral extent. They commonly show a wedge geometry in cross-section. <--v--> ## Thrust Faults and Tectonic Units ### Nappe Terminology 2  <!-- .element style="width:90%" --> <--v--> ## Thrust Faults and Tectonic Units ### Nappe Terminology 3  <!-- .element style="width:90%" --> <--o--> ## Thrust Faults and Tectonic Units ### Autochthons and Allochthons  <!-- .element style="width:60%;float:right; margin-left:50px;" --> **Allochthon** refers to nappes or tectonic units that have been transported. **Autochthon** designate in-situ rocks or tectonic units that have *not* been transported, i.e. basement rocks. Locally transported rocks are referred to as **parautochthonous**. The low-angle fault or shear-zone that separates allochthon from autochthon is called a **detachment** or **décollement**. <--o--> ## Thrust Faults and Tectonic Units  <!-- .element style="width:100%" --> The directions and orientations of structures within nappes often refer to the hinterland or foreland. The **hinterland** designates the central mountainous region of the orogen, wheres the **foreland** occupies the margins <--o--> ## Thrust Faults and Tectonic Units Thrust nappes are characteristics of orogen such as the Alps and the Caledonian-Appalachian Orogen.  <!-- .element style="width:100%" --> *Cross-section through the Alps, Schmid and Kissling, 2000* <--o--> ## Thrust Faults and Tectonic Units ### Hinterland characteristics  <!-- .element style="width:100%" --> - Thick-skinned deformation, meaning both basement and cover (wedge) are involved. - Penetrative deformation - Formation of large metamorphic nappes. - Extensive internal folding of the nappes is common. <--o--> ## Thrust Faults and Tectonic Units ### Foreland characteristics  <!-- .element style="width:100%" --> - Thin-skinned contractional tectonics. - Very localized deformation. - Formation of nappe systems. - Local basement not involved. - Deposition of sediment following erosion of the hinterland. <--o--> ## Thrust systems geometries <div> <div style="width:50%; float:left"> Thrust typically propagates in a stepwise manner that gives rise to **ramp-flat geometries**. **Flats** form along soft, incompetent layers. **Ramps** develop where the thrust cuts across relatively stiff layers. Ramps categories are based on their orientation relative to the direction of transport. - Frontal ramps are perpendicular with reverse dip-slip. - Lateral ramps are parallel to the direction of transport. They are associated with vertical transfer faults. - Oblique ramps form oblique slip faults. </div> <div style="width:50%; float:right">  <!-- .element style="float: right" width="100%" --> </div> </div> <--o--> ## Thrust systems geometries Contractional faults in the foreland of an orogenic zone typically form **imbrication zones** and **duplex structures**. <div> <div style="width:50%; float:left"> **Imbrication zones** results from the formation of ramps. They are composed of a series of **horses** thrusted up along more or less parallel ramp faults. Imbrications zones form preferentially in the foreland. - Repeated series of thrusts sharing a dip direction - Faults flatten out into the basal thrust (décollement) - Fault dip depends on erosion level - Blind thrust: No surface expression </div> <div style="width:50%; float:right">  <!-- .element style="float: right" width="100%" --> </div> </div> <--o--> ## Thrust systems geometries <div> <div style="width:50%; float:left"> Contractional faults in the foreland of an orogenic zone typically form **imbrication zones** and **duplex structures**. **Duplexes** are structures confined between an overlying **roof thrust** and an underlying **floor thrust**. **Duplexes** comprise a series of juxtaposed ramps that formed in front of a propagating floor thrust. It results in stacked **horses**. - Form when sub-horizontal thrust propagation “sticks”. - Bound by floor and roof thrusts. - May contain many individual horses. </div> <div style="width:50%; float:right">  <!-- .element style="float: right; width="80%" --> </div> </div> <--o--> ## Thrust systems geometries  <!-- .element style="width="80%" --> *Duplex structure in dolomitic sandstones, Svalbard, Photo Steffen Bergh* <--o--> ## Thrust systems geometries  <!-- .element style="width="100%" --> *Example of Duplex in the south Norwegian Caledonides, Based on Morley. 1986, Haakon Fossen* <--o--> ## Thrust systems geometries  <!-- .element style="width="100%" --> <--o--> ## Thrust systems geometries <!-- .element style="float: right; width="100%" --> *Stages of thrust development in a sandbox experiment. Two thrusts and associated fault propagation folds, after about 31% horizontal shortening.* *These experiments were led by students, supervised by Assoc. Prof. Sandra McLaren, Melbourne University.* <--o--> ## Thrust systems geometries  <!-- .element style="float: right; width="100%" --> *Stages of thrust development in a sandbox experiment. Greater complexity after 56% shortening. The beginning of a new thrust is also apparent at the frontal edge of the “thrust belt”.* *These experiments were led by students, supervised by Assoc. Prof. Sandra McLaren, Melbourne University.* <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Geometry  <!-- .element style="width:100%" --> Orogenic Wedges are wedge-shaped fold and thrust belts formed in association with crustal contraction and orogenesis. Orogenic wedges are thickest in the hinterland and become progressively thinner toward the foreland. <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### The Buldozer model  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:right; margin-left:50px;" --> Snow piling up at the front of a buldozer is a common analogue used to describe the growth of orogenic wedges. The translation and internal deformation of the wedge are driven by lateral compression and thrusting toward the foreland. The whole wedge is translated along a basal detachment, internal nappes are thrusted along floor faults and shear zones. <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Wedge shape: controlling factors At shallow depth, where deformation is brittle, the shape of the orogenic wedge is controlled by: - Friction along the basal detachment - Shear strength of the orogenic wedge - Surface erosion. The combination of these controlling factors can result in a wide range of orogen shapes. <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Controlling Factors: Friction along detachment  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:right; margin-left:50px;" --> High Friction and asociated strain hardening along the detachment may cause deformation to relocate into the wedge. Folding, formation of duplexes and imbrications result in contraction and increase in thickness. <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Controlling Factors: Friction along detachment  <!-- .element style="width:100%" --> <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Controlling Factors: Strength  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:right; margin-left:50px;" --> The internal strength, i.e. the ability to support loading and resist internal deformation also affects the shape of the wedge. Weak orogenic wedges deform and generate topography more easily than strong orogenic wedges. Weak orogenic wedges are more likely to collapse due to increased topographic loading. <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Controlling Factors: Strength Gravity driven deformation occurs when the topographic load exceeds the internal strength of the wedge.  <!-- .element style="width:100%" --> <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Gravity Models Alternative models uses gravity as the most important driving force for the displacement of nappes and orogenic wedges. Three gravity models have been proposed. - The Gliding Model - The Extrusion Model - The Spreading Model <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Gravity Models: the Gliding Model - The basal detachment dips toward the foreland - Nappe displacement do not require any internal deformation.  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:left" -->  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:left" --> <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Gravity Models: the Extrusion Model Deformation is essentially planar. No deformation occurs in the direction perpendicular to the direction of displacement. **Pure Shear** Deformation  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:left" -->  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:left" --> <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Gravity Models: the Spreading Model The wedge spreads out radially and therefore deforms internally by non-planar deformation.  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:left" -->  <!-- .element style="width:50%;float:left" --> <--o--> ## Orogenic Wedges ### Models Models that explains orogeny and large-scale thrusting must consider gravity driven deformation as well as pure dynamic shortening.