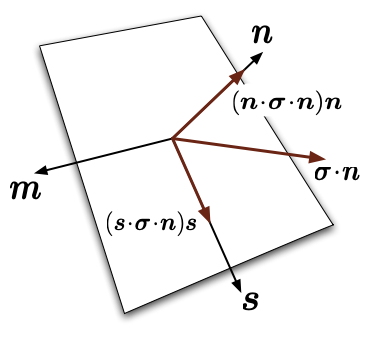

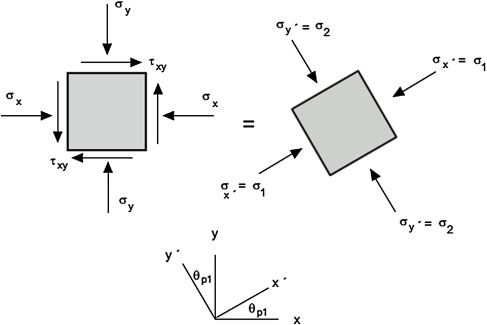

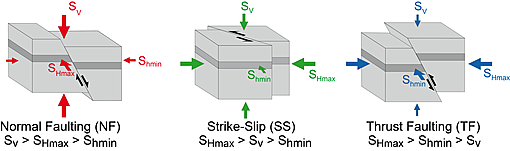

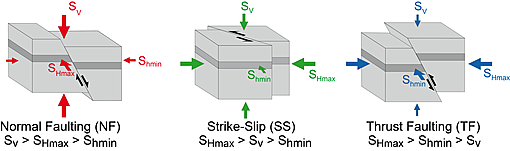

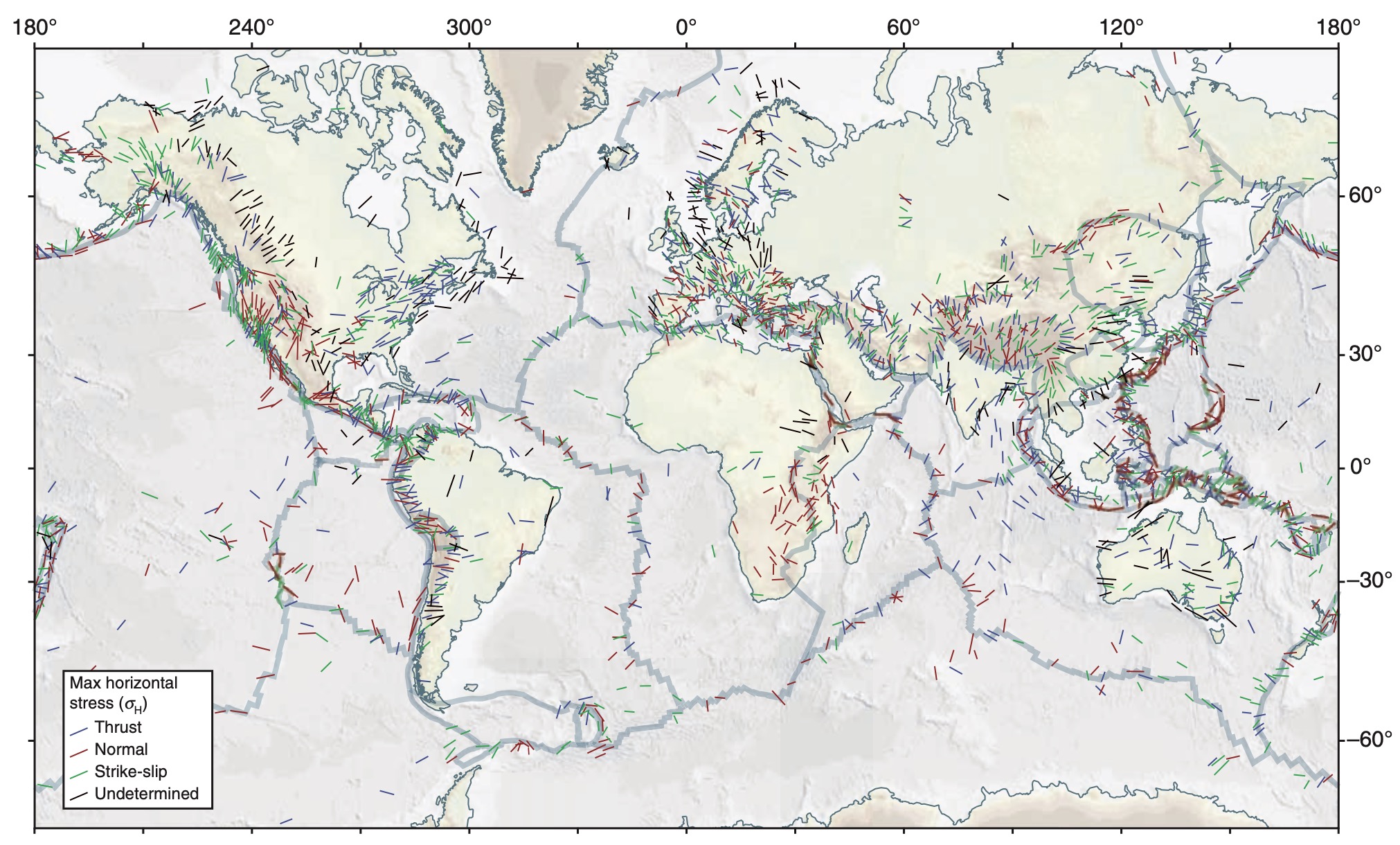

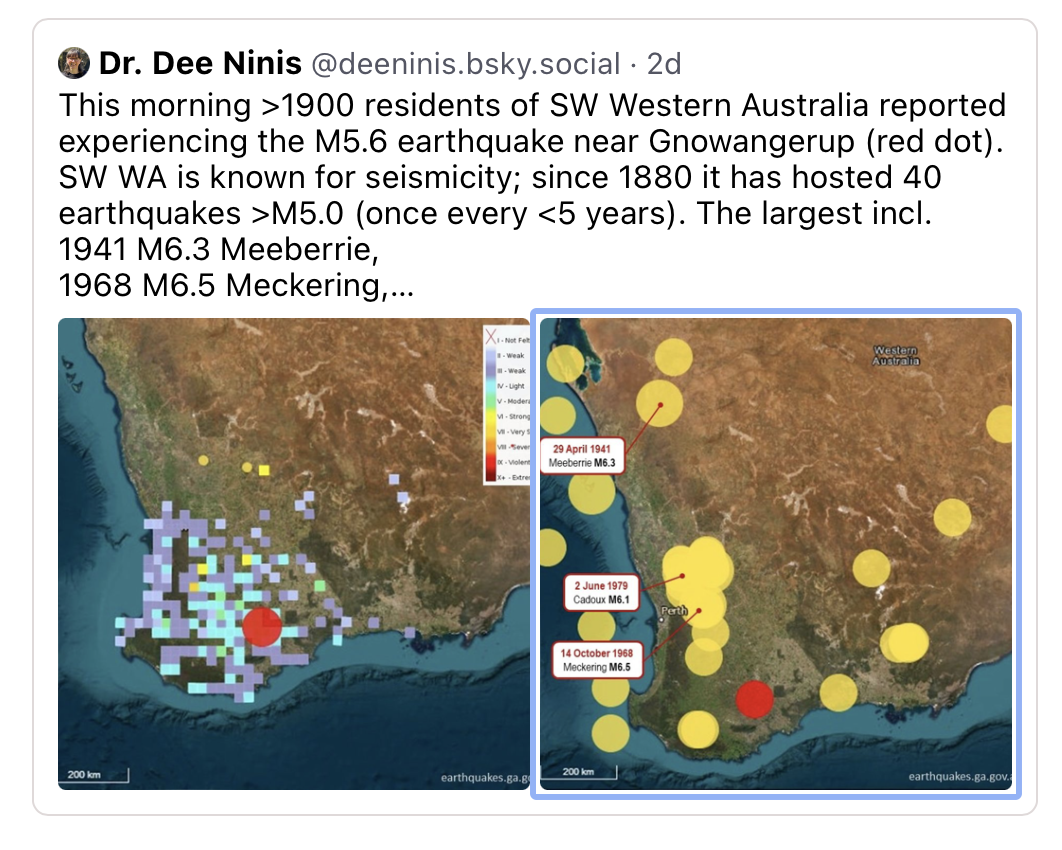

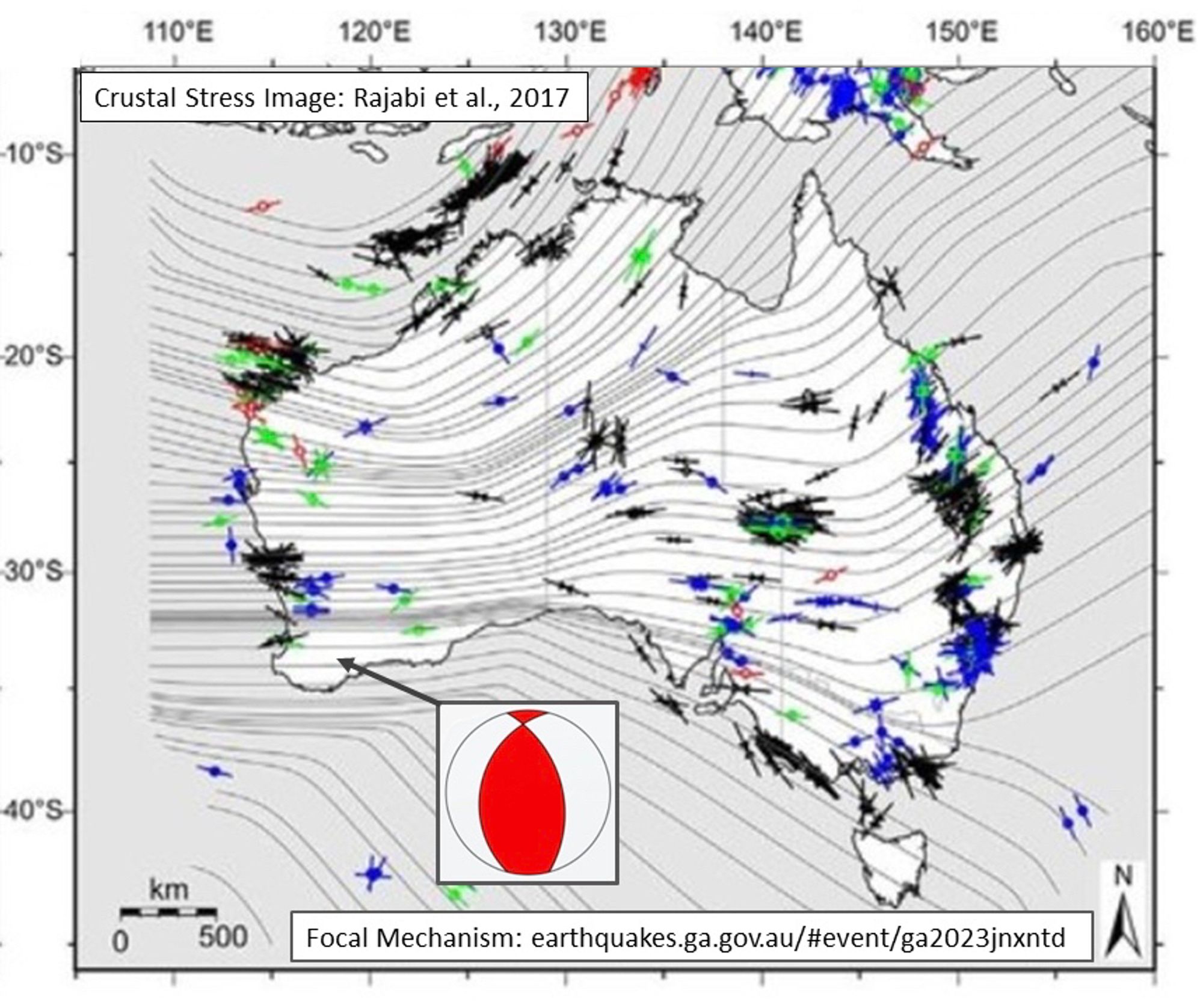

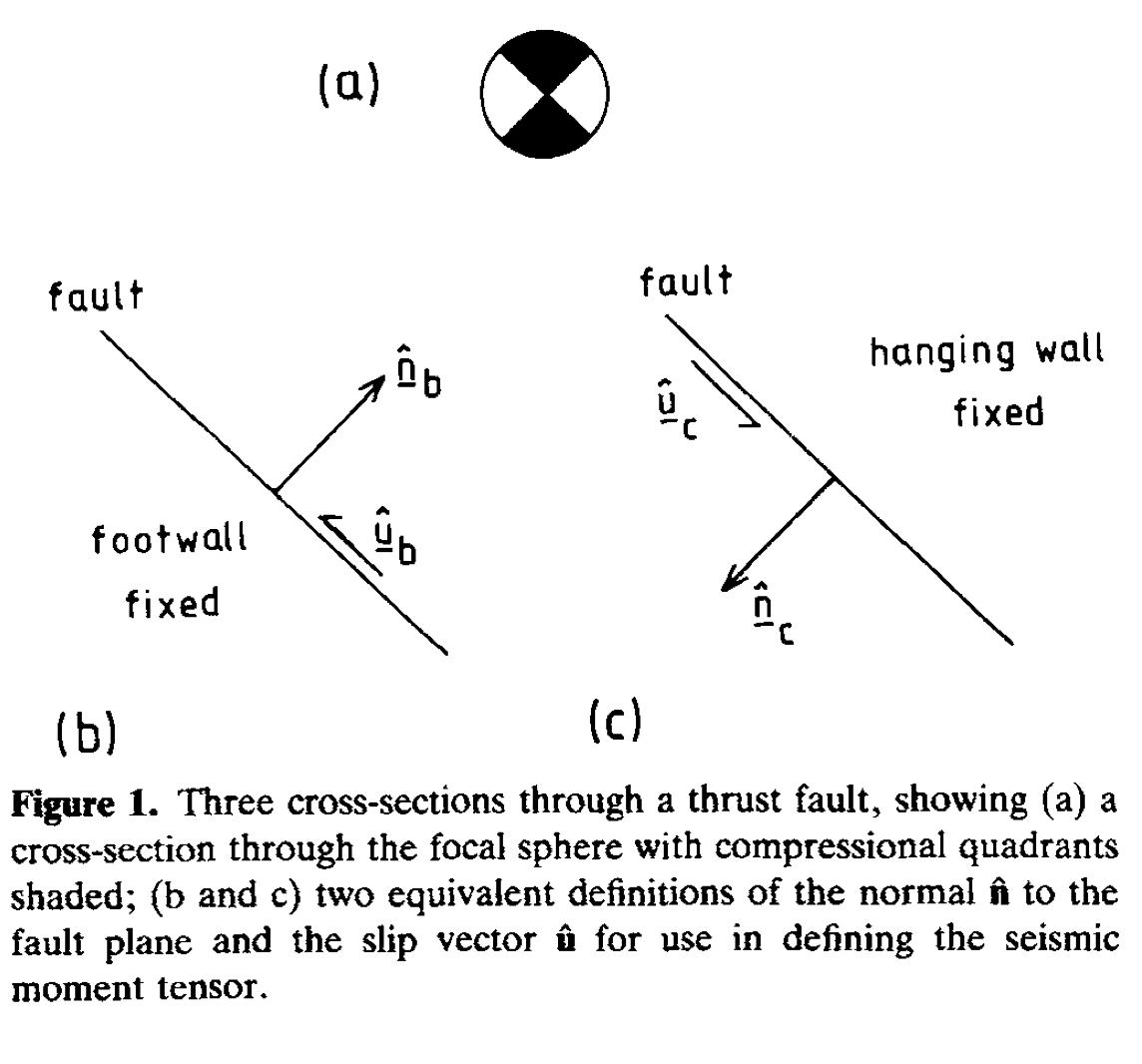

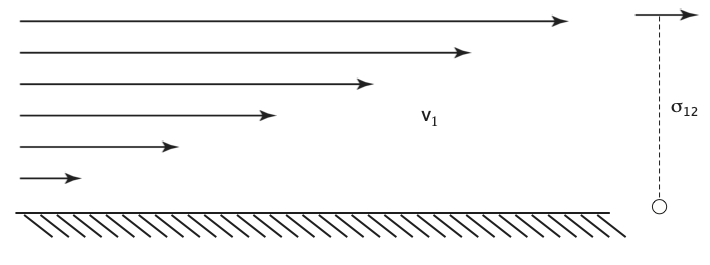

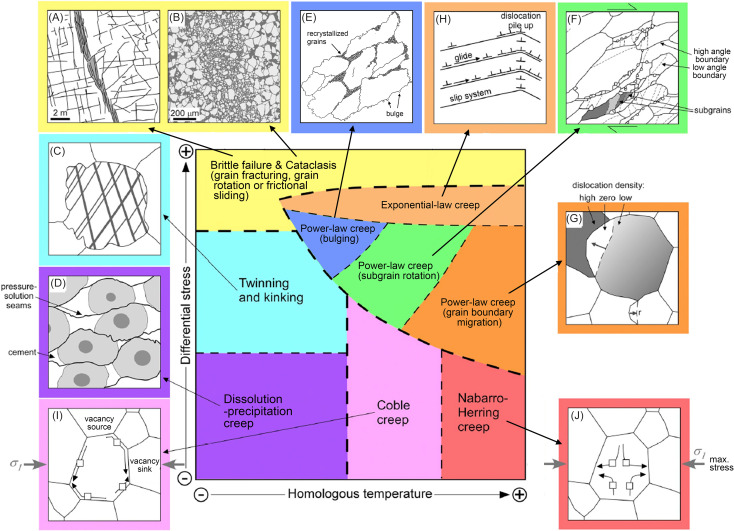

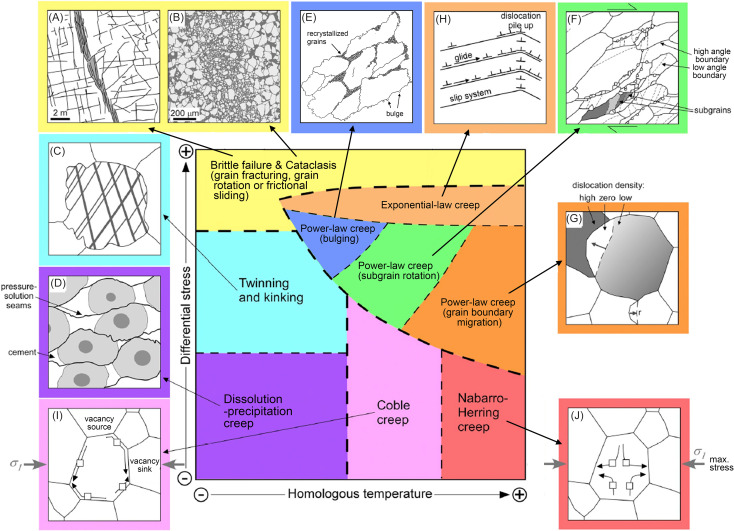

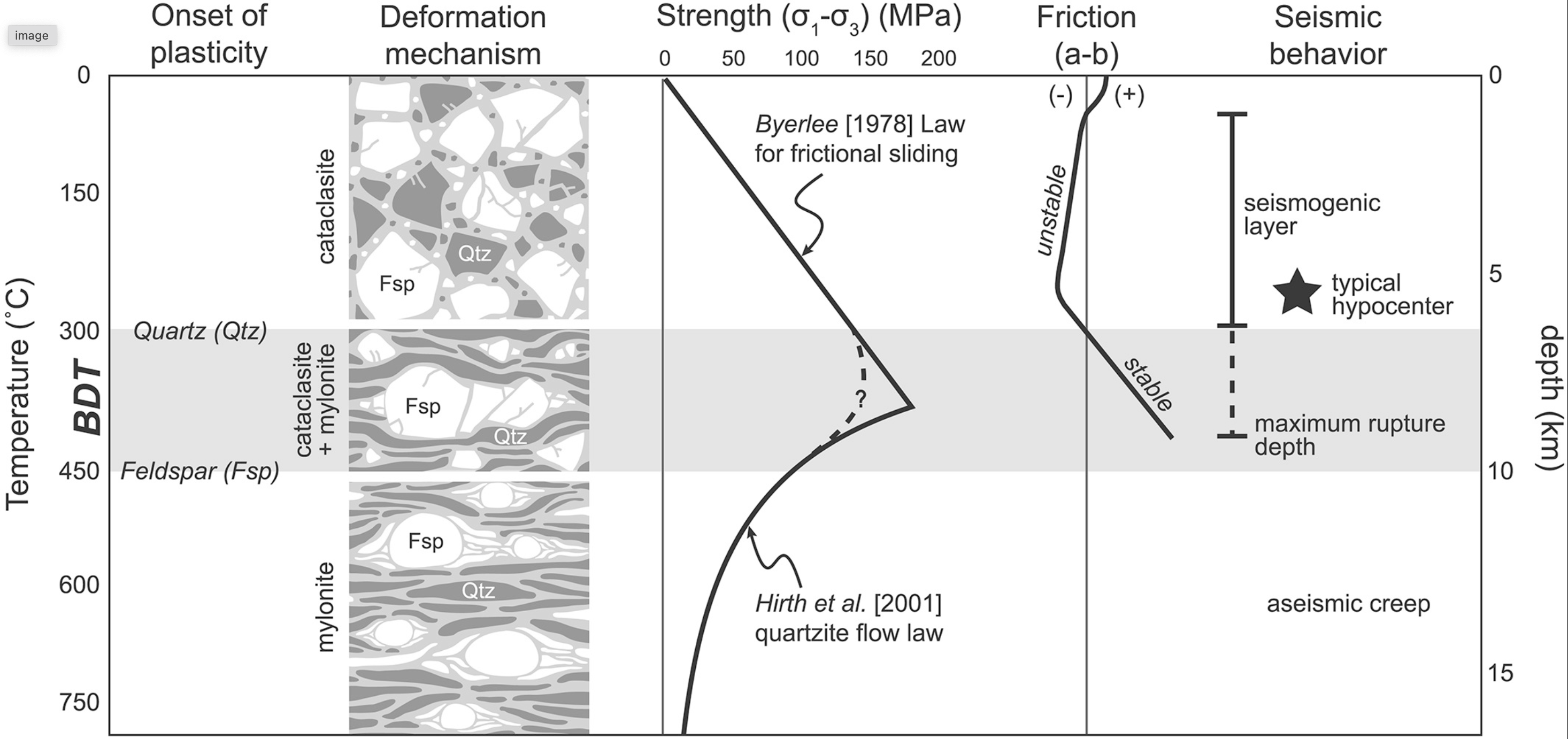

# EMSC 3002 ## Module 1.3 - Stress, Strain and Strength - **Louis Moresi** (convenor) - Chengxin Jiang (lecturer) - Romain Beucher (former lecturer) - Stephen Cox (curriculum advisor) Australian National University _**NB:** the course materials provided by the authors are open source under a creative commons licence. We acknowledge the contribution of the community in providing other materials and we endeavour to provide the correct attribution and citation. Please contact louis.moresi@anu.edu.au for updates and corrections._ <--o--> ## About this section This section covers some of the concepts that we will deal with in considerable detail in Module 3 of the course. You will need to understand the basics of stress, strain, strain-rate as well as elastic, viscous and plastic deformation in order to appreciate the way tectonic stresses produce structures in the Earth. You also need familiarity with the variety of structures in the Earth before you can appreaciate how stresses and constitutive properties of rocks play out under different situations. This will be a brief introduction and we will return to details once you have completed Module 2. <--o--> ## What is Stress ? Consider what happens when we build an underground structure - a basement, a trench, a tunnel or a mine. What is the most important thing we have to do to remain safe ?  <!-- .element style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto; width:50%" --> In the shallowest parts of the crust, confining pressure is low and the strength of the soil is correspondingly weak. It fails by collapsing sideways. <small> (See [*Homes damaged in Mount Waverley construction site collapse 'still unsafe'*](https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-10-16/homes-still-unsafe-after-mount-waverley-pit-collapse/6858266)) </small> <--v--> ## What is Stress ?  <!-- .element style="float:right; margin-left:20px; width:33%" --> The exposed, vertical surface used to be in equilibrium with its surroundings: all forces were in balance and we can only ensure no movement takes place if we supply equivalent forces. Here, the most important forces are the horizontal ones that hold the walls in place. We can replace these by horizontal supports. Please remember this if you become a paleoseismologist or an archeologist (or a builder / civil engineer), or if you are building a retaining wall on your property one day. <small> ( See this [*wikipedia article on trench shoring*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trench_shoring)) </small> <--v--> ## What is Stress ? In a deep structure, the dominant forces change and the engineering response changes accordingly. <center>  <!-- .element style="width:50%" --> </center> Now the dominant forces are vertical because the weight of the over-burden is so large. The first task is to support these loads when material is removed. <small> From [Roof Support in Coal Mines](https://www.culturenlmuseums.co.uk/SIModes/Detail/14223) from the North Lanarkshire Museums collection. </small> <--v--> ## What is Stress ? Of course, the **magnitude** of those forces is also much larger and there is a limit to how deep it is possible to tunnel and still support an open void. <center>  <!-- .element style="width:66%" --> </center> <small> For an explanation of this image, see [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cave-in](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cave-in) </small> <--o--> ## The Stress Tensor  <!-- .element style="float:right;width:49%%" --> <div style="width:45%; margin-left:50px;"> The stress has a distinct orientation as well as magnitude. Here are some examples that we will commonly encounter in tectonics A. Pure shear with the most compressional direction vertical. Typical of a region undergoing extensional deformation. B. Pure shear with the most compressional direction horizontal. Typical of a region undergoing compressional deformation. C. Simple shear (e.g. a zone of strike-slip deformation viewed from above) D. Pressure (increase) </div> <--v--> ## The Stress Tensor If we cut out a plane through a material that is under stress, then there is a **traction vector** (a force) on this plane that results from the unbalanced stresses and *the vector changes with the orientation of the plane*.  <!-- .element style="float:right;width:49%%" --> In fact, this is enough to define the stress tensor. $$ T_i = \sum_{j} \sigma_{ij} \times n_j = \boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{n} $$ where $\left\\{ n \right\\}$ is the vector normal to the plane. Here is a way to think about it: *In general, the force that we need to balance in a void in the ground will be in a different direction for the roof from the walls* Pressures are stresses (forces acting per area of a surface) and so stresses have the same units: $\textrm{Pa} \equiv N / m^2 $ <--v--> ## The Stress Tensor The complexity we have seen reflects the fact that **stress is a tensor quantity**. $$ \mathbf{\sigma} = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_{xx} & \sigma_{xy} & \sigma_{xz} \\\\ \sigma_{yx} & \sigma_{yy} & \sigma_{yz} \\\\ \sigma_{zx} & \sigma_{zy} & \sigma_{zz} \end{bmatrix} $$ The stress tensor is **symmetric**. i.e. $\sigma_{xy} = \sigma_{yx}$ It has a **volumetric** component (pressure) that is independent of the orientation and a **deviatoric** component (the shear stresses) that is not. We can rotate the coordinates (equivalent to adjusting our point of view) and in one specific orientation, the shear stresses all vanish. This coordinate system defines the principal stresses. <--o--> ## Principal Stresses The stress tensor has **principal directions** which define a special orientation in which the shear stresses all vanish (this is a property of tensor quantities in general - they can be diagonalised). <center>  <!-- .element style="width:40%" --> </center> This will be very helpful in understanding tectonic stresses, however, it may be hard to find what these directions are. This is something we address in our theory module. <small> The diagram above is found in Kaliakin, V. N. (2017). Stresses, Strains, and Elastic Response of Soils. In Soil Mechanics (pp. 131–203). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804491-9.00004-5 </small> <--v--> ## Principal Stresses & Tectonics The surface of the Earth is a **free surface**. That is, it is not confined by stresses but evolves to an equilibrium where there are no resulting stresses. There can be no shear stresses. <center>  <!-- .element style="width:80%" --> </center> This means that one principal stress has to be normal to the Earth's surface (close to vertical) and two tangential to the surface (horizontal). The orientation of the principal stresses dictates the fault orientation most likely to form and also controls which faults are likely to be the first to slip (orientation, weakness). Broadly, we can categorize the regional stress field by the orientation of the principal stress and hence the tectonic regime. <--v--> ## Principal Stresses & Tectonics Faults form and are most likely to slip when they are oriented at a shallow angle to the most compressive principle stress direction. <center>  <!-- .element style="width:80%" --> </center> This minimises the normal stress on the faults and maximizes the shear stress. This angle is dictated by the friction coefficient. $$ \tan 2\theta = \mp \frac{1}{\mu} $$ <--v--> ## Global Stress Revisited  <!-- .element style="float:right; margin-top:50px;margin-bottom:50px; width:50%; margin-left:50px" --> The World Stress Map (WSM) 2016 displays the contemporary crustal stress orientation in the upper 40 km based on the WSM database release 2016. Lines show the orientation of maximum horizontal stress. The colours indicate whether stresses are: - Normal faulting ($\sigma_1$ vertical ) - Strike slip ($\sigma_2$ vertical) - Thrust faulting ($\sigma_3$ vertical ) <--v--> ## Australian Stress Field <center>  <!-- .element style="height:400px" -->  <!-- .element style="height:400px" --> </center> Analysis of the M5.6 WA earthquake, August 2023 in the light of the Australian stress field (trajectories) <--o--> ## What is Strain ? Strain is the relative change in length/shape of a material as a result of deformation. It has no units as it is a relative measure (but often expressed in terms of % strain)  <!-- .element style="float:right;width:35%" --> In one dimension, this is simple to express: $$ \varepsilon = \frac{\delta L}{L_0} $$ In three dimensions, like stress, it is actually a tensor. We already saw the diagram on the right to describe the orientations of the stress and the tendency to deform from those stresses (in an isotropic material). $$ \mathbf{\varepsilon} = \begin{bmatrix} \varepsilon_{xx} & \varepsilon_{xy} & \varepsilon_{xz} \\\\ \varepsilon_{yx} & \varepsilon_{yy} & \varepsilon_{yz} \\\\ \varepsilon_{zx} & \varepsilon_{zy} & \varepsilon_{zz} \end{bmatrix} $$ <--v--> ## Strain Tensor The strain tensor contains volumetric strains, shear strains and normal strains. The shear and normal strains are the the **deviatoric** parts of the tensor. These are analogous to the shear stresses and normal stresses of the deviatoric stress tensor. The components of the strain tensor are usually expressed this way: $$ \varepsilon_{ij} = \frac{1}{2} \left[ \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial x_j} + \frac{\partial u_j}{\partial x_i} \right] $$ Where $u_i$ is the displacement in the direction $i$. $i,j$ can be any of $\{1,2,3\}$ and the coordinates $\{x,y,z\}$ are then referred to as $\{x_1, x_2, x_3\}$ (etc). A typical component might be written $$ \varepsilon_{xy} \equiv \varepsilon_{12} = \frac{1}{2} \left[ \frac{\partial u_1}{\partial x_2} + \frac{\partial u_2}{\partial x_1} \right] $$ <--v--> ## Symmetry of the Strain Tensor From the definition given, it is clear that $\varepsilon_{xy} \equiv \varepsilon_{yx}$. The strain tensor is the **symmetric part** of the more general deformation tensor and this removes all components of the deformation that are associated with pure **rotation**. Rotations are equivalent to changes in the point of view of the observer and we know that the forces and responses cannot depend on the coordinate system itself. This principle is known as **objectivity** - our systems of equations cannot include translations and rotation of the coordinate system. *It is possible to have equations that are sensitive to rotation but these also need additional conservation equations, physical moduli and forces* <--v--> ## Volumetric Strain and Incompressibility The volumetric strain (or dilatation) on a material is given by $$ \delta = \frac{\Delta V}{V_0} = \sum_{i} \varepsilon_{ii} $$ In an incompressible material (an idealised situation, not unlike the notion of a rigid plate), the volumetric strain is always zero (identically zero). Engineers often have a sign convention that differs from the everyday one. Here, increasing volume is considered positive (so an increasing pressure should produce a negative volumetric strain) <--o--> ## Invariants of the (Strain) Tensor Tensors have a number of *invariants*, properties that do not change with the coordinate system. We have met one example already: $$ \delta = \frac{\Delta V}{V_0} = \sum_{i} \varepsilon_{ii} = \sum_{k} \epsilon_k $$ where $\epsilon_k$ represents the principle strains which are unique for the tensor no matter what coordinate system it is expressed in. This is known as the **first invariant** of the tensor, often $I_{\varepsilon}$ The **second invariant**, $II_{\varepsilon}$ is defined as $$ II_{\varepsilon} = \frac{1}{2} \left( \epsilon_1 \epsilon_2 + \epsilon_2 \epsilon_3 + \epsilon_1 \epsilon_3 \right) $$ This plays the role of the magnitude of the deviatoric part of the tensor and that is why it is used when we plot the world strain rate map. <--o--> ## What is Strain-Rate ? The strain-rate a measure of the rate of change of strain with time (of course it is !). The strain rate tensor is sometimes written as $\dot\varepsilon$, but we will refer to $\mathbf{D}$ (see note below) $$ \mathbf{D} = \begin{bmatrix} D_{xx} & D_{xy} & D_{xz} \\\\ D_{yx} & D_{yy} & D_{yz} \\\\ D_{zx} & D_{zy} & D_{zz} \end{bmatrix} \quad \textrm{or} \quad D_{ij} = \frac{1}{2} \left[ \frac{\partial v_i}{\partial x_j} + \frac{\partial v_j}{\partial x_i} \right] $$ Here we have replaced the dispacement vector in the strain, $\mathbf{u}$ with the velocity vector, $\mathbf{v}$ and all other remarks we made about the strain still hold. The strain rate is a symmetric tensor and there are principal strain rates all shear values vanish. The diagonal sums to zero if the material is incompressible (a.k.a zero trace, first invariant is zero). The second invariant is defined from the principal values and represents the magnitude. <small> **NB:** the definition of $\partial \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} / \partial t$ is ambiguious because, in some derivations, we don't just differentiate the displacement to get a velocity, we also account for the distortion of the original coordinate system during deformation. That's why we start with velocity gradients etc. </small> <--v--> ## Advanced: Velocity Gradient, Vorticity The strain rate is the symmetric part of a more general **velocity gradient tensor** which can be written $\nabla \mathbf{v}$ (the *gradient of a vector* and not to be confused with $\nabla \cdot \mathbf{v}$, the divergence). $$ L_{ij} \equiv \left( \nabla\mathbf{v}\right)^T = \partial v_i / \partial x_j \quad \\{i,j\\}:\\{1,2,3\\} $$ Which means you may see the strain rate written like this: $$ \mathbf{D} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\nabla \mathbf{v} + \left( \nabla \mathbf{v} \right)^T \right) \equiv \frac{1}{2}\left(\mathbf{L} + \mathbf{L}^T \right) \quad \textrm{and} \quad \mathbf{W} = \frac{1}{2} \left(\mathbf{L} - \mathbf{L}^T\right) $$ Here $\mathbf{W}$ is the spin tensor. It is related to the better known **vorticity** vector, $\omega$ through $$ \omega_i = -\epsilon_{ijk} W_{kj} = 2\Omega $$ $\Omega$ is the angular velocity at each point in the fluid. Hence the names "spin" and "vorticity". <small> The wikipedia article is quite good: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strain-rate_tensor Smith, A. C., & Kaloni, P. N. (1996). A note on spin, vorticity and the deformation-rate tensor. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics, 62(1), 95–98. https://doi.org/10/dfxhjj </small> <--o--> ## Kostrov Summation links seismicity / strain There is a connection between the seismic moment tensor and the strain rate tensor which is attributed to Kostrov (1974).  <!-- .element style="width:30%;float:right; margin-left:30px;" --> The moment tensor can be interpreted as: $$ M^n_{ij} = M^n_0 \left(u_i n_j + u_j n_i \right) $$ where $\mathbf{\hat{u}}$ and $\mathbf{\hat{n}}$ are unit vectors describing the slip direction and the normal to the slip plane respectively (see diagram) $$ \left< \varepsilon \right>_{ij} = \frac{1}{2 \mu V} \sum_n M^n _{ij} \quad \textrm{or} \quad \left< D \right> _{ij} = \frac{1}{2 \mu V \tau} \sum_n M^n _{ij} $$ Here, $\tau$ is a time over which we summing the moment tensor to create a time-average. $\left< . \right>$ denotes an average over the volume, $V$. <small> Jackson, J., & McKenzie, D. (1988). The relationship between plate motions and seismic moment tensors, and the rates of active deformation in the Mediterranean and Middle East. Geophysical Journal International, 93(1), 45–73. https://doi.org/10/fp7rkq Kostrov, V.V., 1974. Seismic moment and energy of earthquakes, and seismic flow of rock. Izv. Acad. Sci. USSR Phys. Solid Earth, 1, 23–44. </small> <--o--> ## Rheology Rheology is the study of how materials deform / flow in response to stresses. We do not know *a priori* how a material will behave when stressed and how this will change with temperature and pressure. We can make some educated guesses but there are empirical coefficients that we have to measure. - When a material deforms as an elastic medium, there is a relationship between stress and strain and elastic "constants" such as shear / bulk modulus. - When a fault slides under shear stress, there is a frictional relationship that describes when sliding begins - When a material deforms as a viscous fluid, there is a relationship between stress and strain-rate and the viscosity and bulk viscosity are the relevant coefficients. $$ \sigma_{ij} = C_{ijkl} \varepsilon_{kl} $$ The coefficients should be (rank 4) tensors because there is no particular reason to expect all the stress and strain directions to respond the same way. But symmetry is helpful and usually we work with simplifications. <--v--> ## Rheology: Elasticity  <!-- .element style="width:35%;float:right;margin-left:40px;" --> The one dimensional elastic response to stress is the classical Hooke's law for an extending spring. This is typically a linear response but if the stress is too high, permanent deformation or failure may occur. In general, $$ \sigma_{ij} = \color{Blue}{2\mu \varepsilon_{ij}} + \color{Red}{\lambda \delta_{ij} \varepsilon_{kk}} $$ where the term in Red term is the volumetric strain but the term in Blue is not purely deviatoric because it still contains the diagonal terms. <--v--> ## Rheology: Elasticity  <!-- .element style="width:40%;float:right" --> $$ \sigma_{ij} = \color{Black}{2\mu D_{ij}} + \color{Black}{\lambda \delta_{ij} D_{kk}} $$ If we apply a single normal stress component, it is clear that there must still be a response in all three dimensions (two in the sketch), especially if the material is incompressible, or very nearly so. <--o--> ## Rheology: Viscosity <center>  <!-- .element style="height:250px;" -->  <!-- .element style="height:250px;" --> </center> **Viscosity** is a measure of the resistance of a fluid to deform under shear stress. It is commonly perceived as "thickness", or resistance to flow. Viscosity describes a fluid's internal resistance to flow and may be thought of as a measure of fluid friction. Water is runny, having a lower viscosity, while honey is "thick" having a higher viscosity. The symbol we typically use for viscosity is $\eta$ (sometimes $\mu$ but we often use that for elastic shear modulus !) *The right image is from the University of Queensland [Pitch Drop Experiment](https://smp.uq.edu.au/pitch-drop-experiment)* <--v--> ## Rheology: Viscosity  <!-- .element style="width:35%; float:right; padding-left:30px; " --> Viscous deformation is an irreversible *flow* that occurs in response to an applied shear stress. The stress is found to depend on the strength of the shearing *velocity gradient*. $$ \tau_{ij} = \eta D_{ij} $$ <!-- .element style="width:60%;" -->  <!-- .element style="width:35%; float:right; padding-left:30px;" --> Think of this as the stress that resists the shear deformation, i.e. how hard it is to stir the fluid. This is much harder if the fluid is **more viscous**. Or think of it as how fast the fluid responds to a given force (e.g. gravity) so a viscous gravity current will spread **more slowly** if the viscosity is high. Viscosity only opposes the formation of velocity gradients; not a driving force, only a resistance. <--v--> ## Rheology: Viscosity  <!-- .element style="width:35%;float:right;margin-left:40px;" --> The idealised, linear relationship between the shear stress ($\tau$) and the deviatoric strain rate, is attributed to Newton but many fluids start to lose their ability to resist at high stress. These are known as thixotropic materials. Rocks can be viscous without being liquid: they deform by migration of defects (dislocations, point defects, grain boundaries) which is often known as crystal plasticity. The changes are permanent and dissipate rather than store energy. Many forms of crystal plasticity weaken at high stresses and this can typically be expressed as a power law. $$ \eta = K \left( II_D \right) ^{n-1} $$ <--o--> ## Rheology: Plasticity <center>  <!-- .element style="height:250px;" -->  <!-- .element style="height:250px;margin-left:60px;" --> </center> Granular materials exhibit "frictional" behaviour. The contacts between grains are locked when the frictional stress ($\tau_Y \approx \mu P$ ) is stronger than any shear stresses. After this, the material will begin to deform and the stresses will be **limited** by the frictional strength. Rocks with multiple faults in them can start to look like granular materials in which the stress is limited by the strength of whichever faults are sliding in the given conditions. If there are very many faults, then the resulting rheological law is likely to be isotropic. $$ \eta = \frac{\tau_Y}{II_D} $$ <--o--> ## Rock Deformation Map  <!-- .element style="display:block; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto; width:50%" --> Rock deformation map that shows how temperature and the magnitude of the differential stress (shear stress compared to confining pressure) influence how rocks deform. <small> Gomez-Rivas, E., Butler, R. W. H., Healy, D., & Alsop, I. (2020). From hot to cold - The temperature dependence on rock deformation processes: An introduction. Journal of Structural Geology, 132, 103977. https://doi.org/10/gk6kn4 </small> <--v--> ## Rock Deformation Map <center>  <!-- .element style="margin-right:5px; height:300px" -->  <!-- .element style="margin-left:5px; height:300px" --> </center> We expect to see far more "creep" dominated deformation in the deep (high pressure, high temperature) parts of the planet and more fracture dominated deformation in the shallow (cooler, lower pressure) parts of the lithosphere. <--o--> ## The Brittle-Ductile Transition Pressure and temperature increasing with depth lead to a well defined increase in strength with depth initially (pressure effect, fault strength) followed by a loss of strength at depth due to increasing temperature promoting creep. <center>  <!-- .element style="width:66%" --> </center> <small> Nevitt, J. M., Warren, J. M., & Pollard, D. D. (2017). Testing constitutive equations for brittle‐ductile deformation associated with faulting in granitic rock. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 122(8), 6269–6293. https://doi.org/10/gbxsbc </small> <--v--> ## The Brittle-Ductile Transition The classic work on the deformation of crustal rocks is Byerlee's paper of 1968. *"... at low confining presure, many rocks are brittle. That is, when differential stress is suffiently high, a fault is formed and, after faulting, the compressive stress is decreased. At high confining pressure, the same rocks may be ductile."* <center>  <!-- .element style="width:66%" --> </center> <small> Byerlee, J. D. (1968). Brittle-ductile transition in rocks. Journal of Geophysical Research, 73(14), 4741–4750. https://doi.org/10/dtqwmx </small> <--o-->